Written by guest blogger Chad Gaffield.

The use of digital technologies is now widespread in historical research, teaching, and societal engagement. This past year of online activity during the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the trend in which historians rely, to varying degrees, on digitally-enabled scholarly practice.

But what does the increasing use of digital technologies mean for historical scholarship? To what extent are there substantive differences between the virtual and physical, or the digital and analog in historical work? And what are the implications for historical practice?

Ever since historians began using computers in the 1950s and 1960s, enthusiasts and critics debated such questions in ways that resonate with today’s discussion of Digital History. This is surprising given the current emphasis on unprecedented technological change. Scholars point to the proliferation of mobile devices, the increasing availability of digitized and born-digital data, and the growing number of easy-to-use applications such as the text reading and analysis tool, Voyant, that are relevant to historical scholarship including undergraduate research.

In contrast, my recent article in the CHR argues that meaningful change in the relationship between History and computers has never been technology-driven; in fact, the invention of increasingly powerful and accessible technologies did not correlate with an increased use in History until very recently. In “Clio and Computers in Canada and beyond: Contested Past, Promising Present, Uncertain Future,” I reinterpret the changing meaning of digital technologies within the dominant disciplinary commitments and institutional conditions of History.

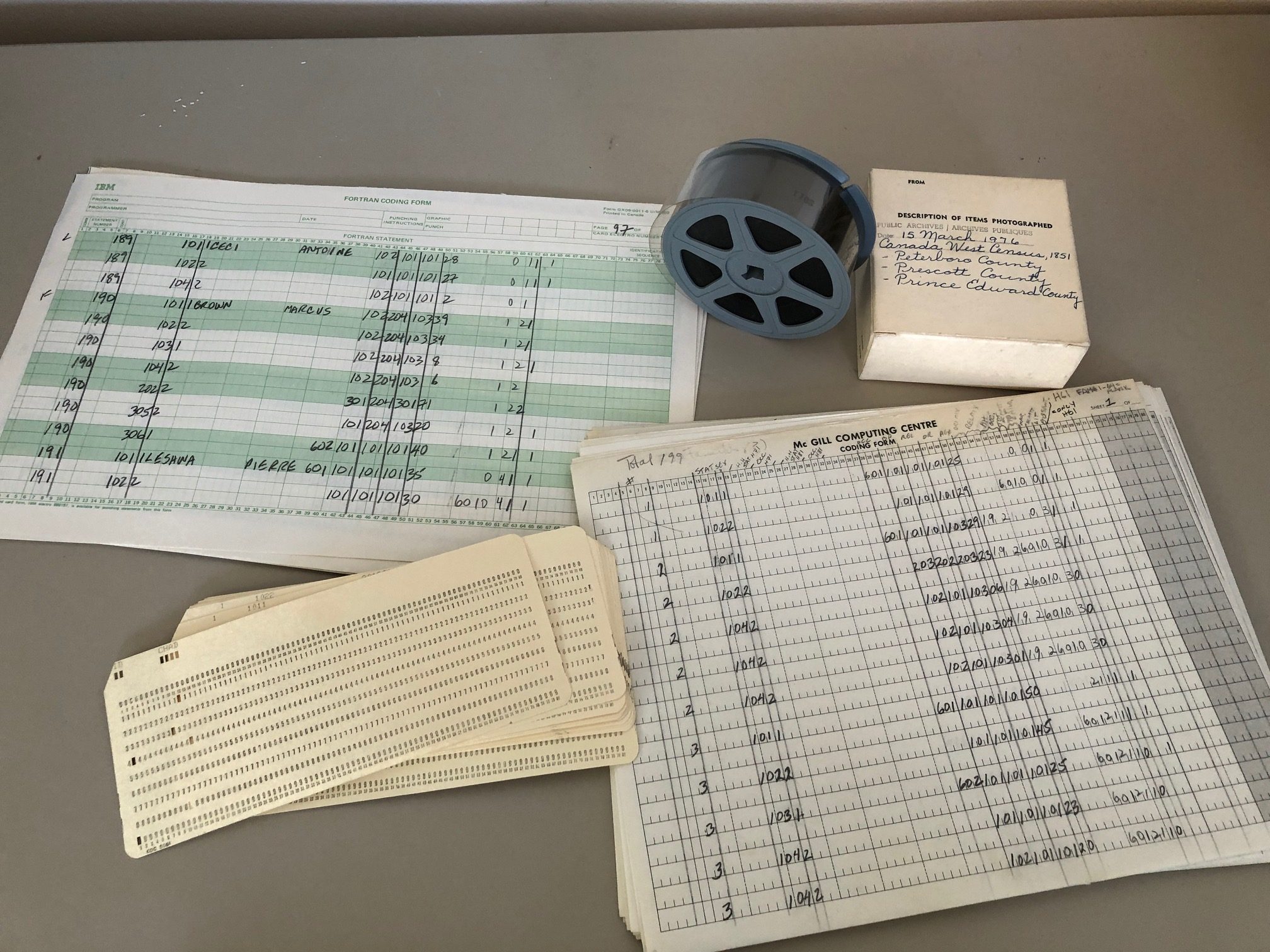

As a contribution to the growing scholarly interest in the history of Digital History, this research project is rooted in my Canada-based experience as a participant-observer of digitally-enabled historical scholarship since I began doctoral studies in the mid-1970s. A glance at my collection of hardware illustrates how rapidly the technology has changed since then, in both expected and unexpected ways.

The first magnetic tapes that I used in the later 1970s replaced my initial boxes of punched Fortran cards and offered exponentially greater capacity while promising an elegant permanence for my historical work.

Image 1: Coding sheets and cards. Image 2: Mag tapes.

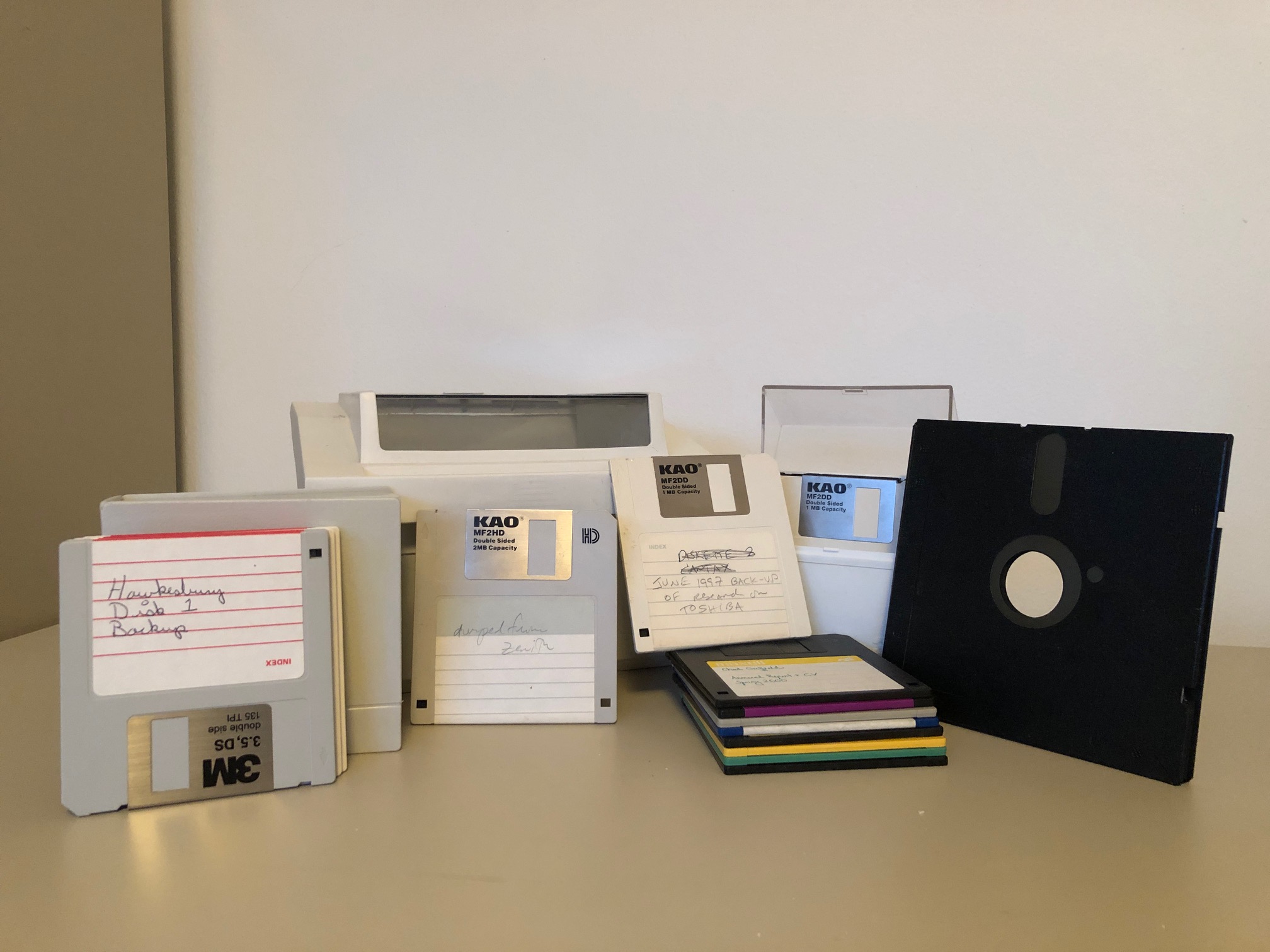

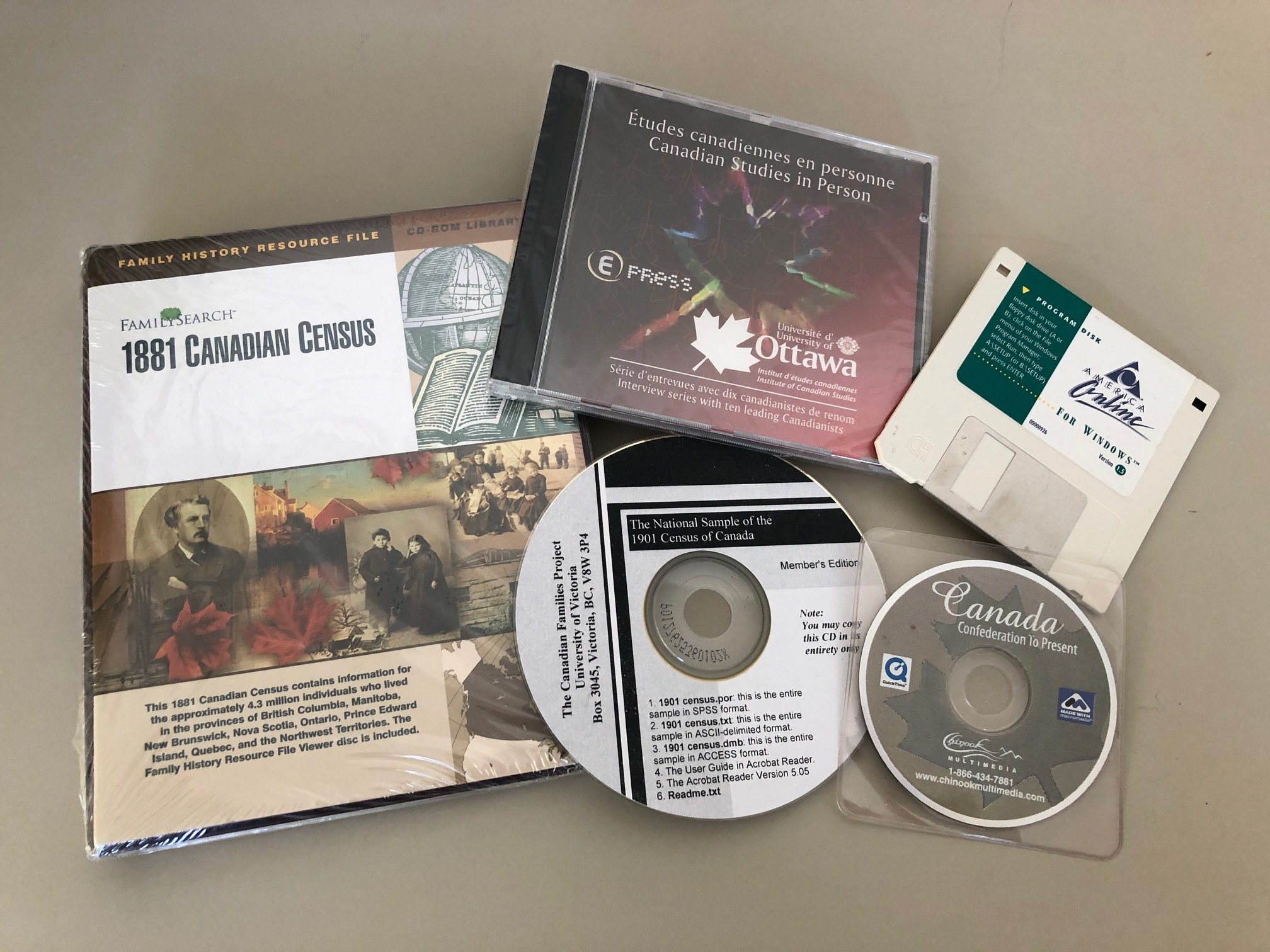

The arrival of microcomputers and diskettes sparked a new sense of personal control and greater accessibility during the 1980s, while the subsequent CDs and DVDs promised to take historical scholarship to a whole new level of immediate evidence-enriched engagement about the past. In comparison to the technologies I have used in the past two decades, this hardware is forgettable and, indeed, largely forgotten as technological changes render them unusable.

Image 3: Diskettes. Image 4: CDs.

But what should not be forgotten is how historians perceived and sometimes used the various computer technologies with consequences that proved to be rewarding, disappointing, surprising, and controversial in ways that are often familiar today. Moreover, the historical evidence that I have examined thus far reveals that many of today’s discussions about Digital History focus on epistemological and ethical issues that earlier generations of historians grappled with as far back as the 1950s. Debates about topics such as digital preservation, control, access, funding, curriculum, interdisciplinarity, collaboration, and scholarly evaluation have long histories with insights relevant to current work in Digital History.

Rarely were computers seen as benign either by enthusiasts or critics. By situating technology in History’s changing disciplinary and institutional contexts, we can better understand how these contexts can both enable and undermine computer-assisted historical scholarship. In this sense, my CHR article invites both reflection on the past and historically-informed engagement with the present to advance Digital History in ways that build upon the core values of historical scholarship.

Chad Gaffield is Distinguished University Professor at the University of Ottawa where he holds the University Research Chair in Digital Scholarship. His recent publications include “Words, Words, Words: How the Digital Humanities Are Integrating Diverse Research Fields to Study People,” Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 5, 2018.

His article, “Clio and Computers in Canada and Beyond: Contested Past, Promising Present, Uncertain Future” appears in the latest issue of the Canadian Historical Review.

The UTP Journals blog features guest posts from our authors. The opinions expressed in these posts may not necessarily represent those of UTP Journals and their clients.

Comments on this entry are closed.