Written by guest blogger Cynthia R. Wallace, Associate Professor of English St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan.

In her 2009 essay “Home,” published in The Source of Self-Regard, Toni Morrison writes, “there is something new and soul destroying about this last and current century. At no other period have we witnessed such a myriad of aggression against people designated as ‘not us’” (20). It would be hard to deny that this aggressive division hasn’t continued to grow in the years since Morrison described it. My question, as a teacher and scholar of literature, is how my own work might respond to what ails us as individuals and societies.

An obvious answer would be to say that reading literature invites and develops empathy, resulting in pro-social behaviors. The ideal of literature as morally uplifting is a very old one, and empathy is a frequently lauded result of reading. But it’s not always this simple: sometimes when we think we’re empathizing, we’re really just projecting our own feelings onto others. And when we do feel with others, our empathy doesn’t necessarily lead to actions that genuinely help. These tensions have given rise to a whole scholarly conversation sometimes called the Empathy Debates.

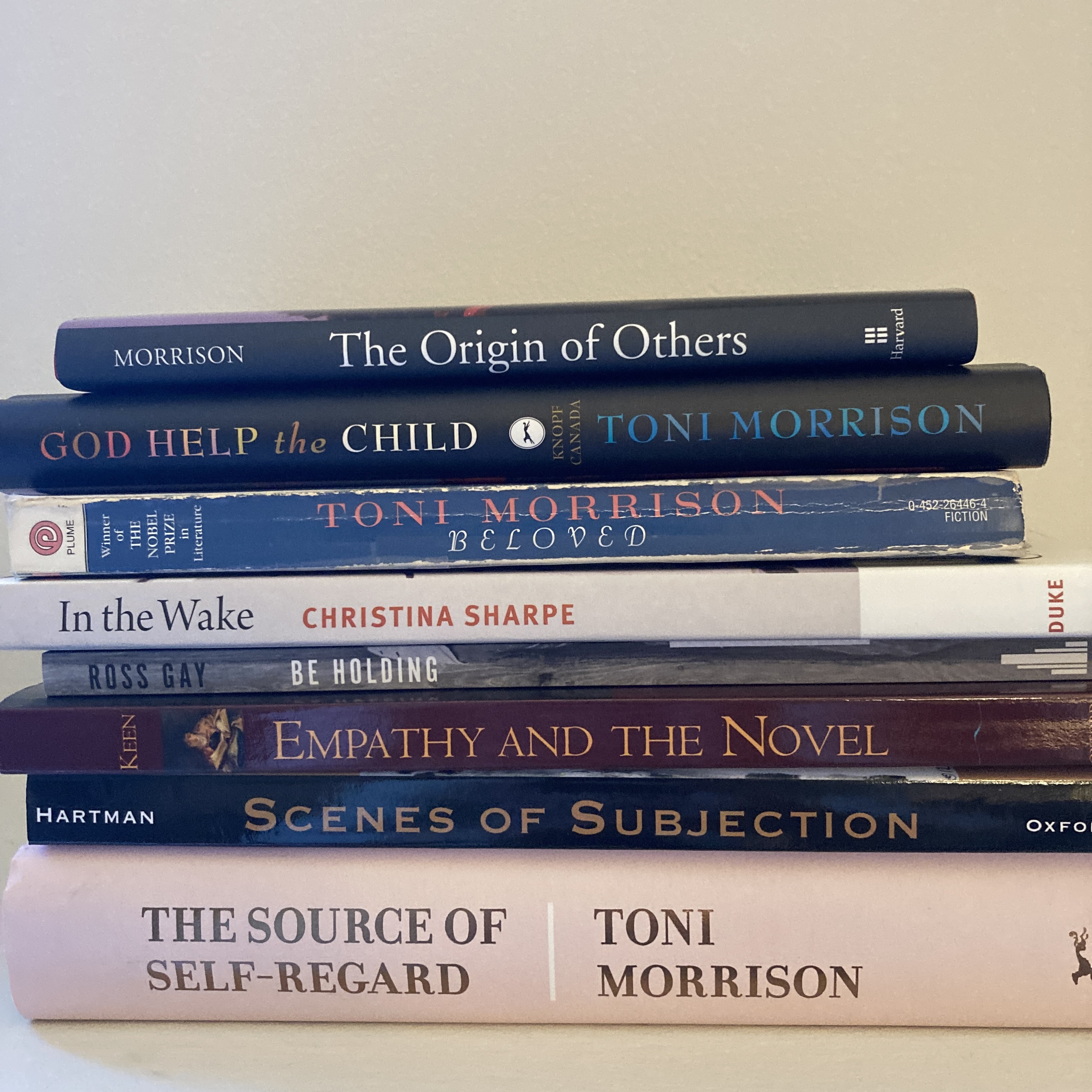

However, Toni Morrison herself wasn’t ready to give up on empathy altogether. She writes compellingly in The Origin of Others about how literature can invite us into other lives: “Narrative fiction provides a controlled wilderness, an opportunity to be and to become the Other. The stranger. With sympathy, clarity, and the risk of self-examination” (91). In novel after novel Morrison risked imagining others’ lives and inviting her readers to join her in that imagining, seeking the core of our shared humanity. At the same time, she refused to sugar-coat the divisions—racism, sexism, ageism, classism—that undermine evolutionary human impulses to feel with and help each other.

My work on Morrison’s last novel God Help the Child brings Morrison’s nuanced representation of empathy into conversation with recent developments in neuroscience and cognitive psychology, showing how research on mirror neurons, structures of empathy, and the outcomes of reading resonates with Morrison’s literary insights and how Morrison’s work challenges the implicit centering of white readers in much of the recent scientific study of readerly empathy.

It extends the work of scholars like Suzanne Keen, who in Empathy and the Novel (2007) forges an interdisciplinary conversation among literary scholars, cognitive psychologists, and neuroscientists interested in the shared question of how literary writing can cultivate empathy and, possibly, ethical behavior. Reading Morrison together with this recent research results in a more complicated story, one that challenges both an outright dismissal of empathy as reading’s goal and a naïve celebration of empathy as the solution to all our current social strife.

Ultimately, bringing Morrison’s work to this interdisciplinary conversation reminds us that science is as indebted to stories as novels are: we can trace back our contemporary conversations about empathy to philosophers who established the “Age of Scientific Racism,” as she calls it in the essay “The Site of Memory.” Now more than ever, scientists and humanists need to forge shared discussions about our brains and our minds, our deepest biases and our deepest hopes, as we pursue something like justice for all, something like a common good.

Cynthia R. Wallace, PhD, is Associate Professor of English at St. Thomas More College, University of Saskatchewan, where she teaches and researches at the intersections of race, gender, religion, and ethics in contemporary literature. Her scholarly work has appeared in journals like African American Review, Contemporary Literature, Religion and Literature, and Humanities, and she contributes literary criticism to the Ploughshares blog. Her book Of Women Borne: A Literary Ethics of Suffering was published in 2016 by Columbia University Press.

Her article, “Reading in the Wake: Empathy Debates, “The Reader,” and Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child” appears University of Toronto Quarterly, Volume 90, Issue 4.

The UTP Journals blog features guest posts from our authors. The opinions expressed in these posts may not necessarily represent those of UTP Journals and their clients.

Comments on this entry are closed.