Written by guest blogger Emily Qureshi-Hurst.

‘Science and religion’ is less a single discipline and more a multiplicity of conversations between faith, its philosophical interpretation, and the empirical sciences. Its overarching aim is to combat the ever-increasing compartmentalisation of academic discourse – as the sciences become more technical, detailed, and specialised, they gravitate away from the natural philosophy out of which they came. In so doing, they deviate from the myriad of disciplinary strands that once made up natural philosophy, including both scientific and theological enquiry. Academia, and the disciplines that are carried out under that name, are, in my view, becoming more fragmented.

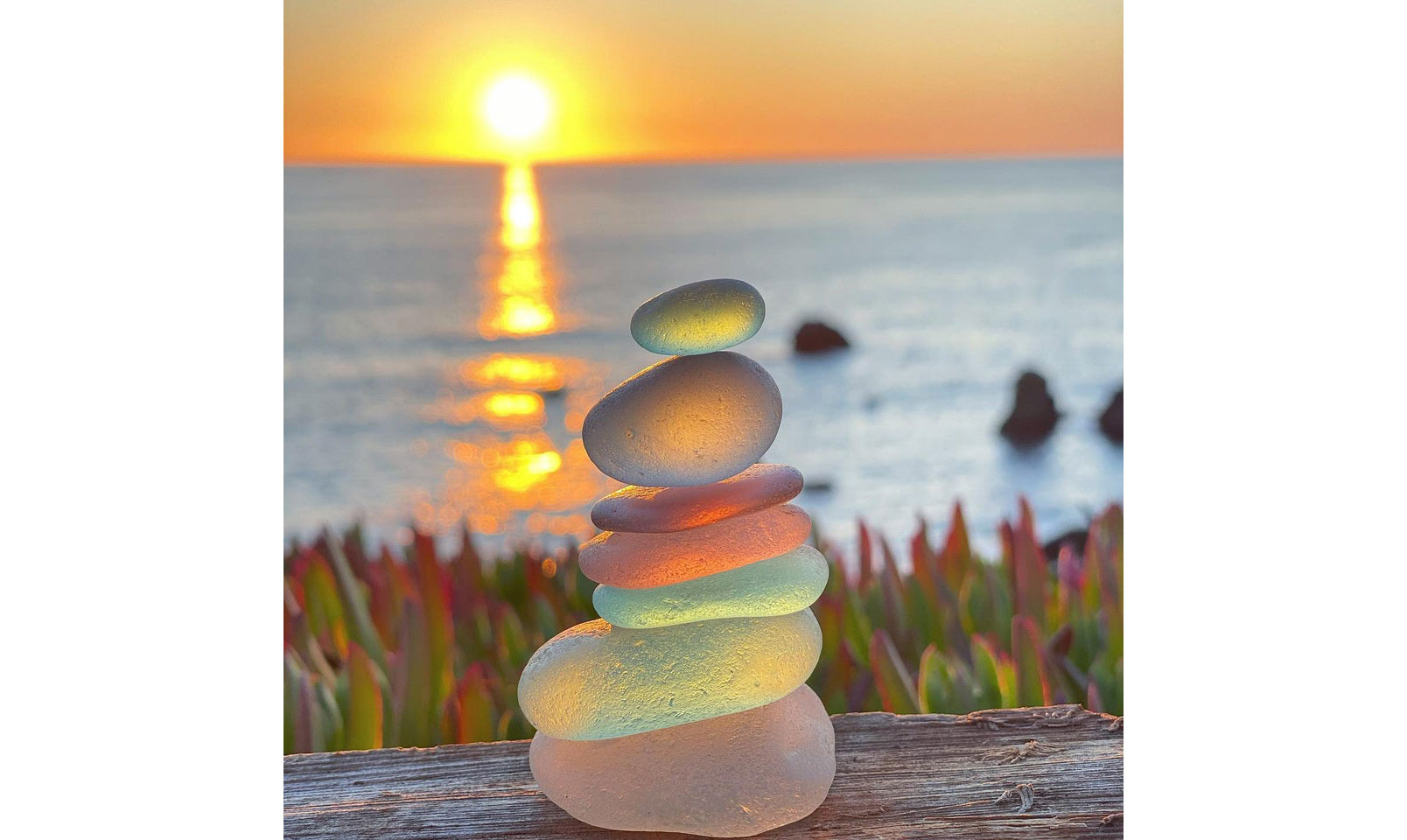

I imagine this process as somewhat akin to a broken bottle on a beach. After it first shatters into shards, the pieces can be easily put back together. Over time, however, as the pieces of glass move with the rhythm of the tides, the edges smooth over and the pieces spread out over larger and larger distances. So too with academic disciplines. The fragmentation of natural philosophy into the self-contained disciplines we see today – physics, mathematics, geometry, metaphysics, theology – has led, over time, to an ever-greater distance between what was once united. Moreover, as the edges of sea-glass become smooth, so too do the boundaries of theology and science. What once fit easily together now seems like it never could have been part of the same larger whole. ‘Science and religion’ is motivated by a desire to reunite this fragmented discourse, reorienting important conversations away from the centre of one’s own discipline and towards a more outward facing approach.

Philosopher Mary Midgely argues that reality is highly complex and comprised of varied terrain. As such, we need multiple maps to accurately represent it. This insight drives scholars engaging in science-and-religion discourse. Neither science nor theology can answer all of life’s most meaningful questions – the best bet is to approach things collaboratively. This is one of the many wonderful features of ‘science and religion’: it is highly amenable to cross-disciplinary collaborations. I have been lucky enough to engage in several of these throughout my academic career so far, and they have led to the most innovative research I have been involved in producing.

My most recent interdisciplinary collaboration, the accompanying article to this blog post, was between a physicist and myself (a philosopher who dabbles in theology). We tackled a cutting-edge finding from quantum mechanics and examined its philosophical and theological implications. Each of us brought invaluable methodological tools to the table, and the result is, we hope, pioneering research in the intersection between faith, philosophy, and physics. Though academic specialisation is growing, and bringing highly detailed, technical, and innovative results along with it, I hope there will always be those of us who walk along the beach picking up and reuniting that which the years have drawn asunder. After all, how else could we come to know the rich and complex reality in which we live?

Emily Qureshi-Hurst is a D.Phil candidate in Science and Religion at the University of Oxford. Her research focuses primarily on the philosophy of time, and how insights from the philosophy of time can enrich the philosophy of religion. She is also interested in the philosophy of physics, particularly the philosophy of quantum mechanics, and has published several papers bringing the philosophy of physics and the philosophy of religion into dialogue.

Her latest article in Toronto Journal of Theology entitled “Quantum Mechanics and Salvation: A New Meeting Point for Science and Theology” is free to read for a limited time here.

The UTP Journals blog features guest posts from our authors. The opinions expressed in these posts may not necessarily represent those of UTP Journals and their clients.

Comments on this entry are closed.