Written by guest blogger Ian Milligan.

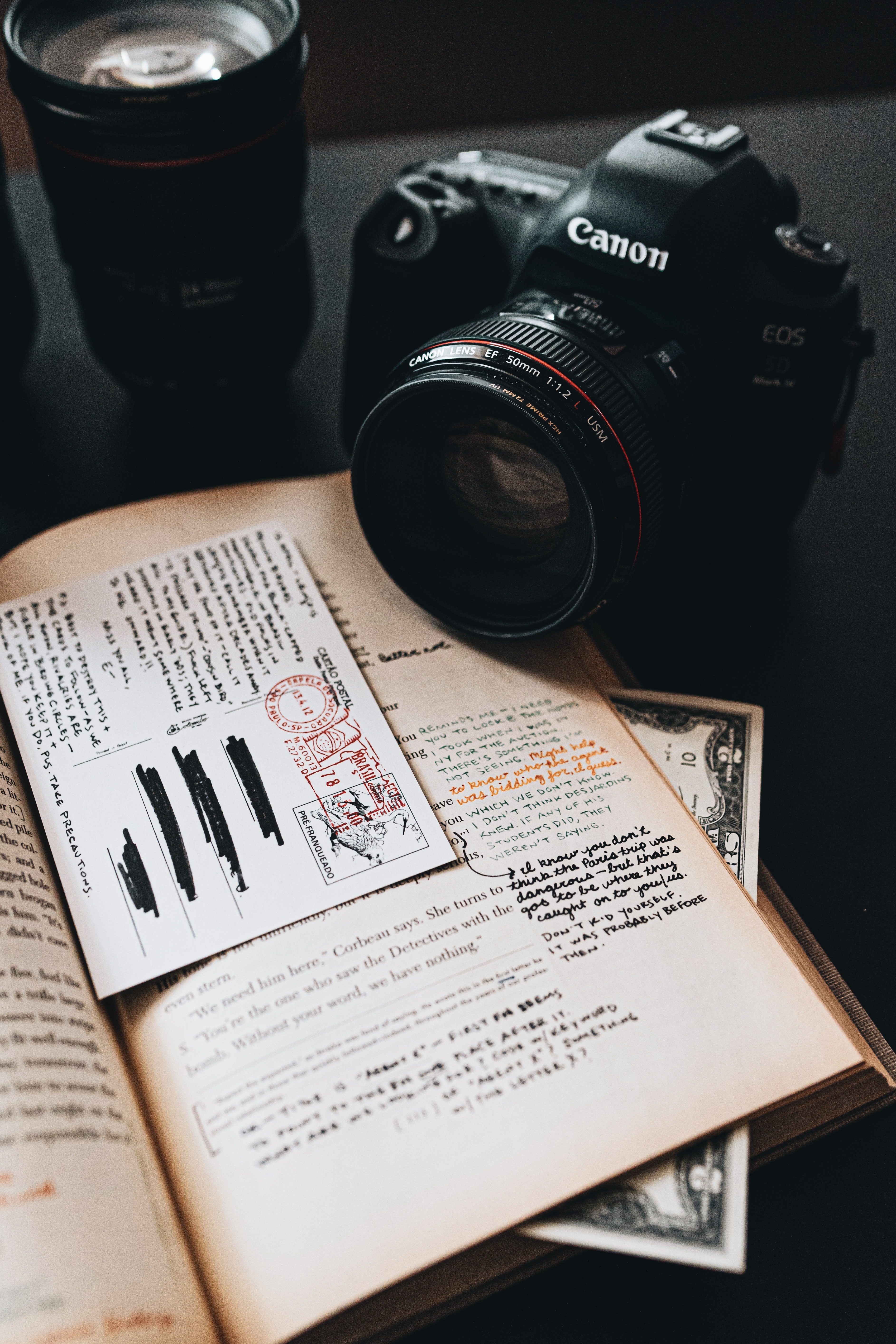

A visit to an archive (when archives were open before the pandemic) looks different than the stereotypical vision of historians slowly pouring over documents. Instead, a visitor would likely see historians hunched over desks, holding smartphones or digital cameras, taking hundreds of photos. Page flip, click, page flip, click, collecting a monumental corpus of information to read once they have returned to their home cities.

My recent Canadian Historical Review article “We Are All Digital Now: Digital Photography and the Reshaping of Historical Practice,” published as part of the Historical Perspectives collection on digital history, explores what this shift means for professional historians and their scholarship. Archival trips have become strategic strikes to let a historian bring home years of documents to read. As so many aspects of the historian’s world has been transformed by digital technology – a theme I also explored in a 2013 Canadian Historical Review article on online databases and their impact on Canadian history – I continue to be curious about how the way in which historians research affects how they understand the past.

I feared that this might be a bit of a niche topic, and was accordingly amazed when I presented an earlier version of this paper at the 2020 American Historical Association meeting and it went “academic viral” thanks to a tweet by Dan Cohen. An article in the Atlantic by Alexis Madrigal summed up the shift well: “the literal job of doing history has changed. It works through screens now; that much is for sure.”

This transformation from notetaking to mass digital photography, to me, exemplifies the fundamental shift in how historians work. Historical work was previously defined by its relationship to the archive, and by virtue of this, also the city in which the archive was. Archival work for most historians was slow, requiring extensive notetaking over weeks or months. This led to tight ties between historians and the places that they studied (a point also made in this article by Lara Putnam).

Consider some hypotheticals. Could one be a French historian without spending much time in France? Or a historian of the Winnipeg General Strike without having been to Winnipeg for more than a few days? Until a decade or so ago, these questions were silly – the sources were generally there and needed to be consulted there. The ability to do quick, surgical photographic changes all that.

This change has profound impact on how historians research and are trained in research. Consider that historians do not receive training in how to use their cameras, have little guidance on how these strategic collection missions should unfold, and most importantly, are often taking photographs in a mad dash. They choose photos to take at the very moment when they may know the least about a project, and follow ups are tougher when documents are consulted far away from the archive.

I conclude my article with the question of whether all historians should be now be considered digital historians. Has the shift towards technology transformed us from a profession based around space and our relationship to going to archives, to a desk discipline? If so, what does this mean for the 21st-century historian?

Ian Milligan is an associate professor of history at the University of Waterloo. He recently published History in the Age of Abundance? How the Web is Transforming Historical Research (McGill-Queen’s, 2019).

His latest article in the Canadian Historical Review entitled “We Are All Digital Now: Digital Photography and the Reshaping of Historical Practice” is available on the UTPJ website.

The UTP Journals blog features guest posts from our authors. The opinions expressed in these posts may not necessarily represent those of UTP Journals and their clients.

Comments on this entry are closed.