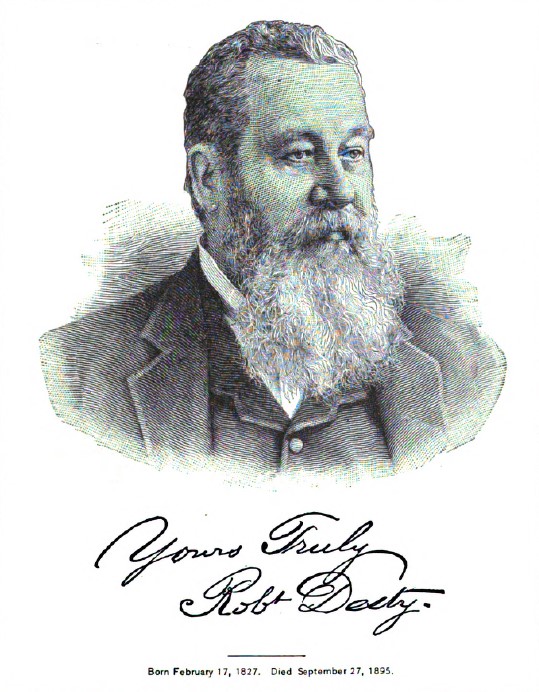

The Canadian-born Robert Desty, eventually a famed legal scholar, who enlisted in New York City in March 1847 (Case and Comment, October 1895).

Written by guest blogger Patrick Lacroix.

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) was a defining event for both belligerent countries. After a vigorous debate over the legitimacy of the war and the right of conquest, the United States acquired a territory of more than one million square kilometres, bringing the nation’s western boundary to the California coast. Mexican territory was thus suddenly halved; the defeat emboldened Mexican advocates of modernization and reform.

The national dimensions of this war easily overshadow its larger international context and the pluralistic character of the fighting forces. In 1845-1846, it seemed more likely that the United States would declare war on Britain over the disputed Oregon Territory. The possibility of conflict did not escape the attention of the British North American colonies, which had served as a battleground in the War of 1812. This, then, was another episode in the troubled course of Anglo-American relations. As it actually played out, the Mexican-American War also said something of international migration in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Nearly half of the soldiers that the United States sent into battle were foreign-born. A large portion came from Ireland and German states. But nearly every polity in Europe was represented—and so were Britain’s colonies. Surviving records suggest that 1,500 “Canadians” (an anachronistic term, but convenient as shorthand) enlisted in the U.S. Army during the war. Some, like the Quebec-born Pie Narcisse Legendre, who was studying law in Exeter, N.H., were already established on American soil when the war began. Others left the homeland specifically to enrol. In late 1846, former Patriote E. B. O’Callaghan met a group of prospective soldiers travelling south from the border; they hoped to soon return with hard American cash in hand.

All British North American colonies were represented in the ranks—from Newfoundland’s seven enlistees to Joseph Clouky (Cloutier) of Red River. More impressive yet are the varied places where these men signed up: locations in New York State and New England, where a larger migration from the colonies was under way, but also farther inland. They enlisted in Pennsylvania and along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Thirteen men sought to join the army in Galena, Illinois. These were areas where a Canadian presence predated the war.

Little qualitative evidence of Canadians’ experience in the ranks is extant. Army schedules help to supplement this obscure area of the historical record. These records invite broader ways of thinking about the Mexican-American War. They are also immensely valuable in helping to define the extent of early Canadian emigrations, with the events of 1846-1848 constituting both a snapshot and a cause of further migration prior to the U.S. Civil War.

Patrick Lacroix, Ph.D., is a scholar of immigration and U.S. religious history. His work has appeared in Histoire sociale/Social History, the Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française, the Journal of Canadian Studies, and other prominent journals.

His latest article in International Journal of Canadian Studies entitled “Canadian-Born Soldiers in the Mexican-American War (1846–48): An Opportunity for Migration Studies” is free to read for a limited time here.

The UTP Journals blog features guest posts from our authors. The opinions expressed in these posts may not necessarily represent those of UTP Journals and their clients.

Comments on this entry are closed.