Written by guest blogger, Kathryn Imray.

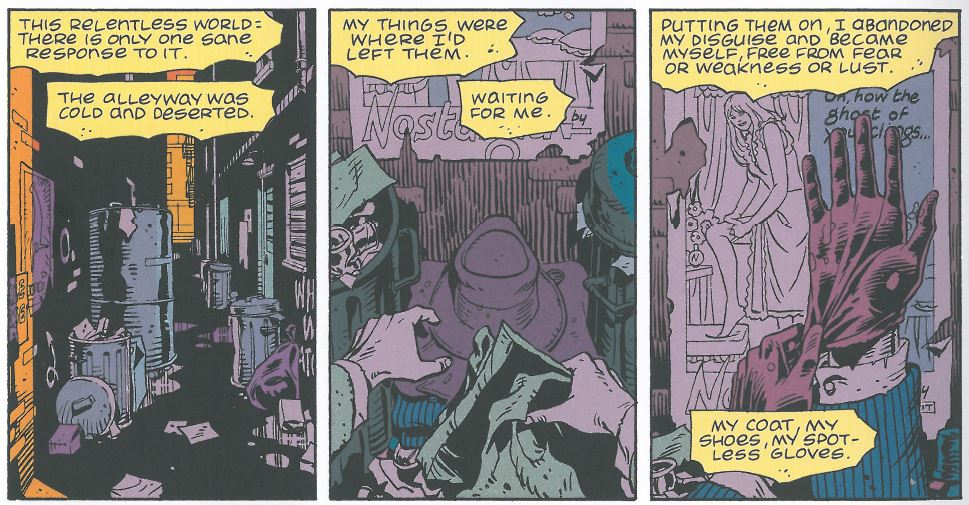

The grown Rorschach’s enemies are ‘lechers,’ communists, liberals, the pampered and decadent, intellectuals, smooth-talkers, heroin users, child pornographers, homosexuals, politicians, ‘whores,’ women who have children by different fathers, and welfare cheats (1:1, 14 16, 19). Some rapists are not acceptable (4:23), others aren’t so bad (1:21). He reads right-wing literature, including the New Frontiersman (7:11), the Watchmen equivalent of Breitbart. His world is a blood-filled gutter (1:1), and there is only one response to “this relentless world” (5:19). Rorschach takes up his mask, gloves, coat, and shoes, dressing himself beneath a poster for Nostalgia (5:19), with the slogan, “Oh, how the ghost of you clings” (see IMAGE 2).

Adrian Veidt sells Nostalgia. Veidt was born rich, but gave it away to become a self-made man. He is “the world’s smartest man,” whose computer password Dan cracks on his second guess. He is a consummate salesman, marketing his image in perfume, hair spray, action figures, and a body building regime (“I will give you bodies beyond your wildest imaginings,” his promotional material says, amid the bodies of his victims [12:6]). He inhabits a large, gold-filled tower, has another large house in the south, and watches a lot of televisions. He wants to be — he knows he is — a great man, and he exploits his sales talents to control the fate of the world, and exploits the world to improve his sales.

Nostalgia is marketed through two slogans: “Oh, how the ghost of you clings” (5:19; 8:25); and, “Where is the essence that was so divine?” (3:7). In a letter to his Cosmetics and Toiletries Director, Veidt writes of Nostalgia:

“It seems to me that the success of the campaign is directly linked to the state of global uncertainty that has endured for the past forty year or more. In an era of stress and anxiety, when the present seems unstable and the future unlikely, the natural response is to retreat and withdraw from reality, taking recourse either in fantasies of the future or in modified visions of a half-imagined past” (unnumbered page, between chapters 10 and 11).

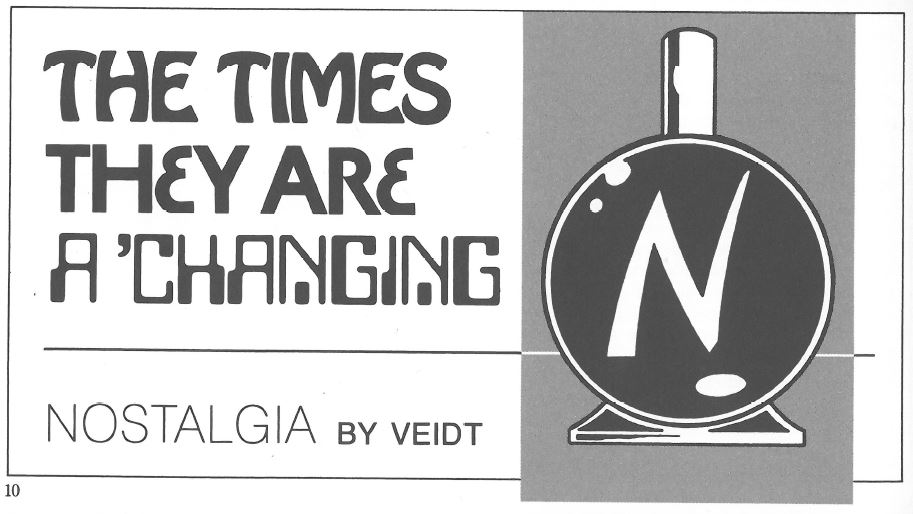

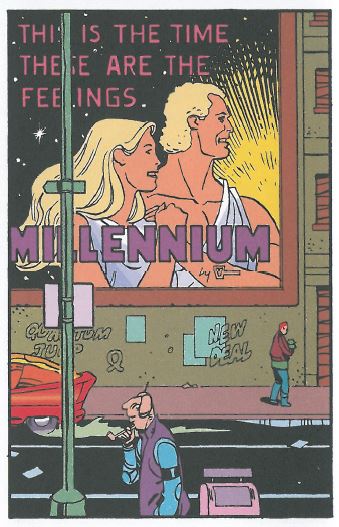

Veidt’s marketing techniques tap into the connection between fear of death and political conservatism. In the future, though, and in anticipation of the peace he plans to bring to the world, the Nostalgia line is to be replaced with a new line, “Millenium” [sic], its imagery “controversial and modern, projecting a vision of a technological Utopia.” The final ad for Nostalgia has a new slogan, “The times they are a’changing,” running from a classic font to a ‘futuristic’ font, and ushering in Veidt’s technological Utopia (see IMAGE 3). Later, amid pro-Russian cultural and culinary artifacts, Veidt’s new perfume is advertised (see IMAGE 4). “Millennium” is written in solid block print across the torsos of two handsome, healthy, heterosexual blondes facing the rising sun. It is an image reminiscent of communist propaganda, and along with the slogan, in a subtly futuristic script, “This is the time. These are the feelings,” rebrands the make-believe of a past age for a future one.

*All references are to the chapter and page in Alan Moore and David Gibbons, Watchmen (Absolute Watchmen), New York: DC Comics, 2005. All images shown are from that edition of the graphic novel.

Kathryn Imray’s article, “Shall Not the Judge of All the Earth Do Right? Theodicies in Watchmen”, is available to read in the latest issue of the Journal of Religion and Popular Culture, Vol. 29, Issue 2 (2017).

IMAGE 2; 5:19, Absolute Edition

IMAGE 2; 5:19, Absolute Edition IMAGE 3; between chapters 11 and 12, Absolute Edition

IMAGE 3; between chapters 11 and 12, Absolute Edition IMAGE 4; 12:31, Absolute Edition

IMAGE 4; 12:31, Absolute Edition

Comments on this entry are closed.