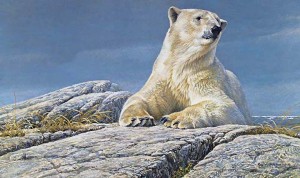

The majestic white bear of the North is now often found in Cineplex previews and TV commercials promoted by WWF and Coca Cola’s combined campaign “Arctic Home,” initiated to help protect polar bears and their habitat from global warming. Of course, before protection efforts were ever underway, it is well known that they were also prized for their fur. What isn’t common knowledge for most is that polar bears were, next to the Queen’s corgis of the last two centuries, the highly sought after royal pets of the Middle Ages.

This endeavour to trap and transform polar bears into pets was considered to be a life of luxury and ease for the polar bear and therefore preferable to their alternate lifestyle. As a prized possession of medieval monarchs, the polar bear was therefore often used by trappers to gain royal favour. Specifically, the inhabitants of Iceland and Greenland were the only men known to have trapped polar bears to train and make pets of them, importing them into Northern Europe and presenting them to various interested kings. As a reward for their services, these northerners often gained either wealth or support, such as ocean-going vessels loaded with merchandise or the funds to establish a bishopric.

While, for the sake of safety, Greenlanders and Icelanders often killed polar bears who wandered into their villages’ outskirts, there are many true and fictional accounts from the annals that portray the polar bear not only as valued commodities but also as benevolent saviours, such as the story of the widow during a famine who was rescued from starvation by a female bear in 1403. Incidentally, the polar bear gave birth to her cubs beneath the widow’s bed and in the process of raising her young until they could fend for themselves, she brought fish and other edibles and gave what was leftover to the widow and her children (Oleson 49).

However, the most famous bear of all is the one in the “rags-to-riches” story of the Icelander, Auđunn, from the Westfjords, who paid for a polar bear with all his possessions so he could present the bear to King Sveinn Ulfsson of Denmark. The short story is akin to the renowned epic poem Beowulf written in Old English. While not as well known, it stands as a tribute to Old Icelandic literature and cultural traditions and, significantly, the special importance placed on the capture and exportation of polar bears.

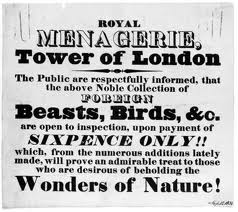

According to Oleson, the polar bear of the Middle Ages can be seen not only as having been an efficient tool of diplomacy among kings but also as a means of fostering geographical knowledge of the lands from whence they came. From diving for fish in Damascus on behalf of the Sultan El-Kamil to stalking the halls of the Tower of London under the rule of Henry III, the great White Bear graced more than just the TV screens and magazine covers of modern day—they were once a esteemed part of the medieval royal entourage.

Find out more about the value of polar bears in the Middle Ages by purchasing and continuing to read T.J. Oleson’s article “Polar Bears in the Middle Ages,” published in the Canadian Historical Review in 1950.

Interested in more under-the-radar topics such as this? Consider subscribing to the Canadian Historical Review and gaining access to its bountiful archives on all things historical!

Comments on this entry are closed.