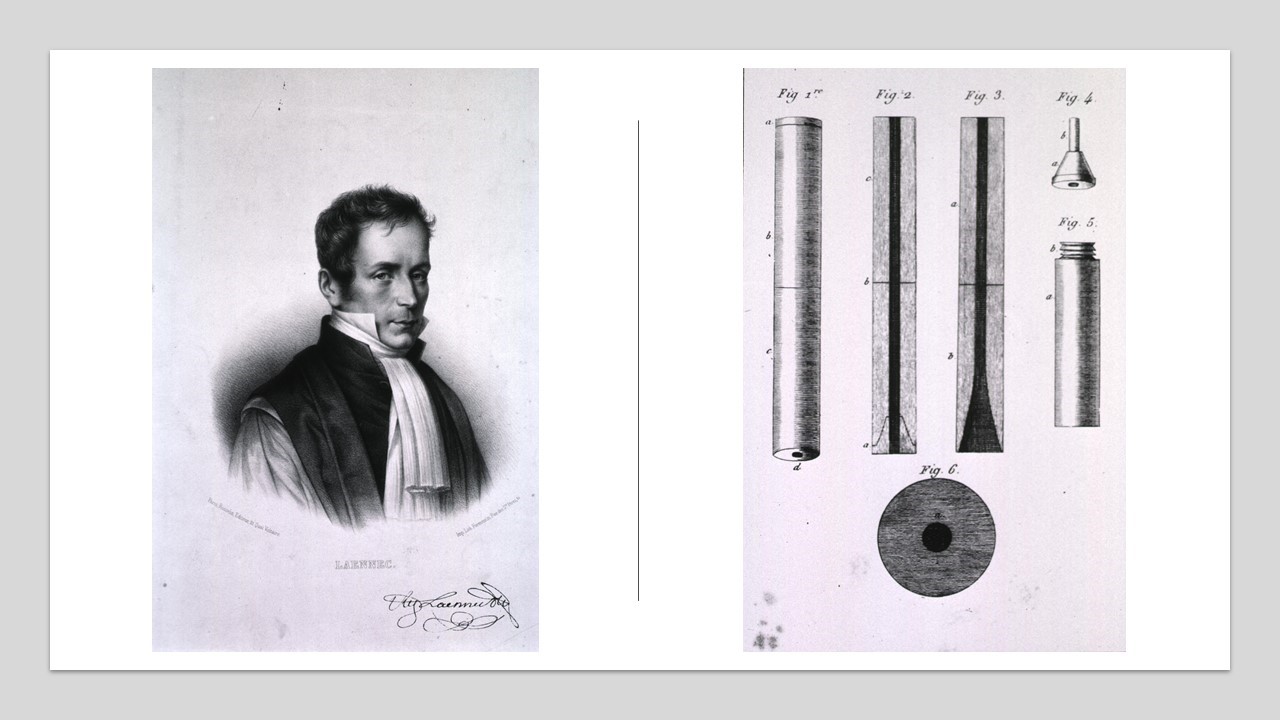

Figure 1. Laennec and His Stethoscope, 1819. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Figure 1. Laennec and His Stethoscope, 1819. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Written by guest blogger Richard Reinhart.

During the span of my cardiology practice beginning in 1980, technology blossomed in the field, particularly with the advent of interventional procedures such as coronary angioplasty, stents, and catheter-based heart valve replacement. Non-invasive technology advanced as well. Cardiac ultrasound became more quantitative, such as being able to measure cardiac dimensions, valve areas and valve regurgitation. Nuclear cardiology scans for measuring coronary blood flow and magnetic resonance imaging for cardiac structure and function came into being.

So, where did that leave the stethoscope and the skills required to interpret findings on auscultation? In my career as a cardiologist I depended on the stethoscope in my daily practice. By the time I graduated from medical school auscultation with the use of the stethoscope was routinely a large part of the curriculum. Sometime in the mid-20th century the stethoscope became the symbol of the medical profession—physicians, nurses, and other allied professionals. Recently there is concern that the skills of auscultation are now in decline because of our reliance on technology.

The stethoscope was not always the symbol of the medical profession. It went through a long period of adoption by American practitioners from the time the stethoscope was invented by the French physician R.T.H. Laennec in 1816 until its more widespread use in the early 20th century.

I found the history of the adoption of the stethoscope to be a particularly interesting part of medical history. To understand this process, I needed to have a better understanding of state of medical training and knowledge and the thoughts and ideas of practitioners during this timeframe. I began this process by searching out primary source material in the form of medical ledgers, case books and diaries of physicians who trained and practice in the 19th century. However, I learned that, although this was interesting, these did not contain enough detail to get an idea what physicians actually did when taking care of patients. A good source of information was the rhetoric displayed in medical journal articles, textbooks, and journal advertisements published during the period under consideration.

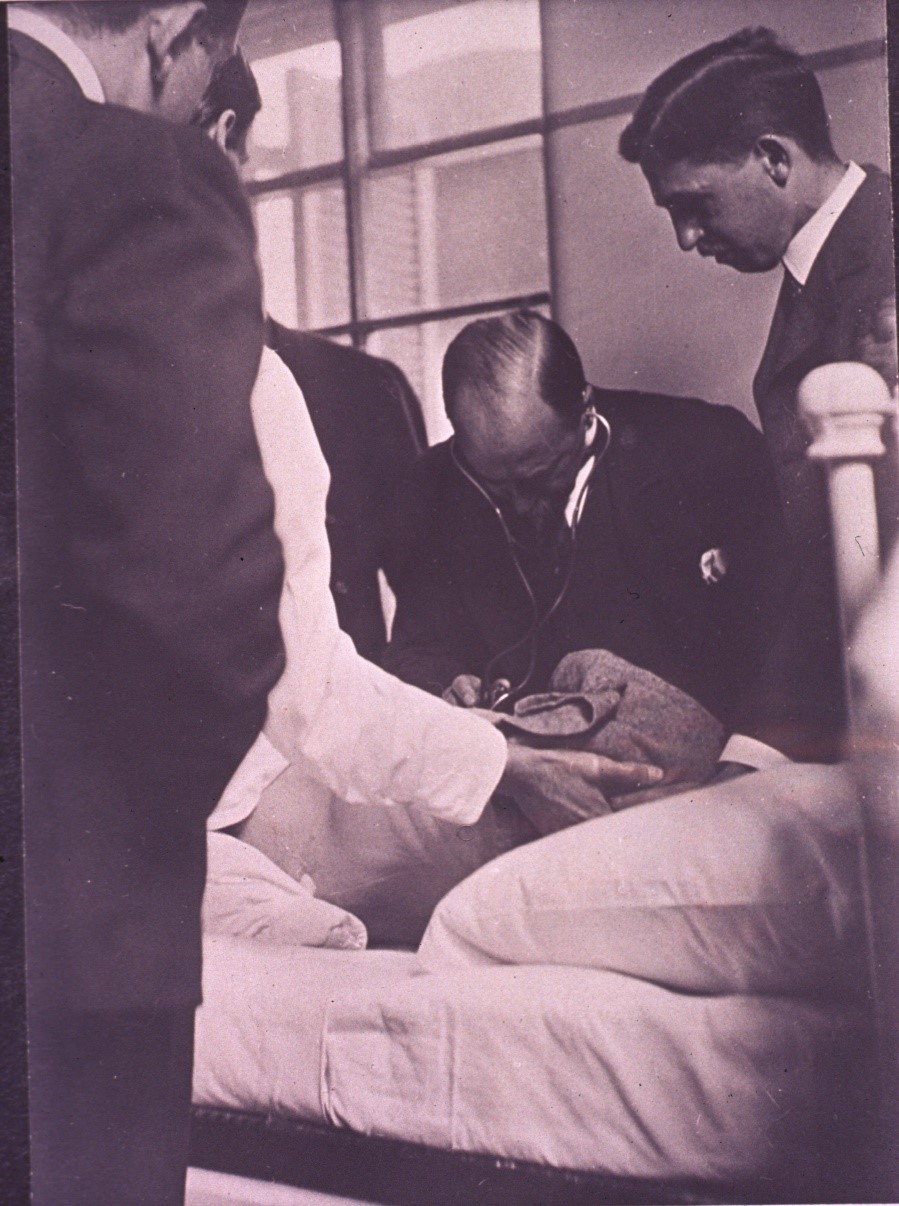

Figure 2. William Osler listens to a patient through a modern binaural stethoscope; medical students are gathered around during teaching at Johns Hopkins, ca. 1903. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

Figure 2. William Osler listens to a patient through a modern binaural stethoscope; medical students are gathered around during teaching at Johns Hopkins, ca. 1903. Courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

The stethoscope evolved in sophistication—from a monaural wood cylinder to a binaural instrument with flexible tubes and adjustable earpieces. This could be seen in medical journal advertisements and articles describing the various forms of the instrument. The figures show the evolution of the stethoscope from Laennec to Osler.

Once the information was gathered, then began the important and complex process of putting it into a format that was publishable and presenting new information. This was a great learning process. Along the way I also learned that in the whole process of data gathering and writing it took the help of many other people.

Richard Reinhart is Emeritus Professor of Medicine at East Carolina University. His professional focus is on clinical practice, teaching and the study of 19th century medical history and medical practice. His latest article in the Canadian Bulletin of Medical History entitled “The Stethoscope in 19th-Century American Practice: Ideas, Rhetoric, and Eventual Adoption” is free to read for a limited time here.

The UTP Journals blog features guest posts from our authors. The opinions expressed in these posts may not necessarily represent those of UTP Journals and their clients.

Comments on this entry are closed.