Written by guest blogger Alex Wermer-Colan.

“Fascism does not prevent speech, it compels speech.”

– Roland Barthes, “Inaugural Lecture,” 1979

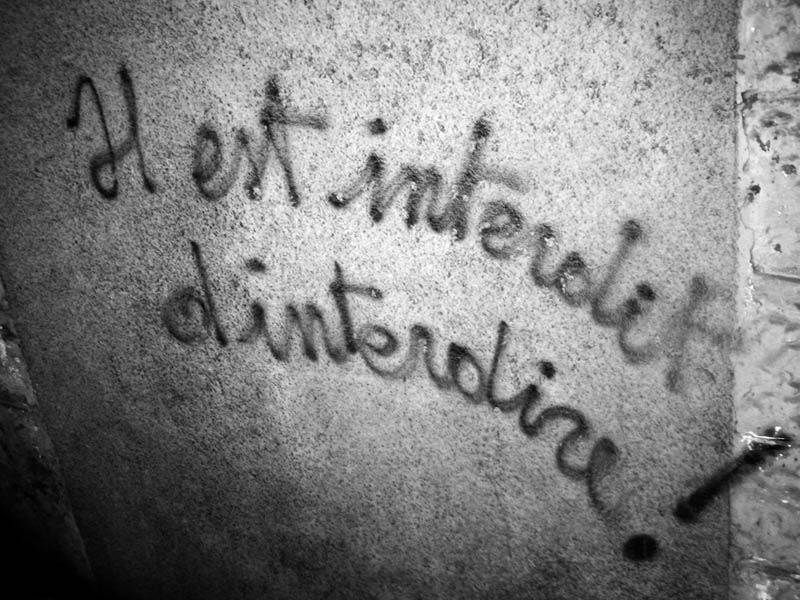

The enigmatic graffiti in the above photo, following Jean Yanne’s coinage of it on the radio, soon spread like a viral meme across the streets of Paris during the revolutionary protests of May 1968. In the half-century since the grassroots insurrection’s historic failure, however, this surreal demand for liberation has been sublimated, insidiously, into our phantasmagoric society of the spectacle. As if invented by a PR firm to promote our consumer culture’s injunction to enjoy, you can now go on Amazon and buy mugs, t-shirts and tote bags appropriating the paradoxical commandment: “It is forbidden to forbid.”[i]

Approximately ten years after the revolutionary events of 1968, the renowned writer and critic, Roland Barthes, took a different perspective on power and freedom, censorship and self-expression, one adamantly at odds with May 1968’s romantic aspirations. In his “Inaugural Lecture” at the Collège de France on January 7, 1977, Barthes famously pronounced: “Fascism does not prevent speech, it compels speech.” From such a vantage-point, the French student protestors’ complaints that Barthes was too aloof from “Mai 68” come into relief as painfully naïve.

During the late 1960s and throughout the 70s, Barthes hardly seemed surprised by the right’s subsequent consolidation of power (for left-leaning U.S. citizens living today under President Donald Trump, the most agonizing event of that time must surely be Richard Nixon’s reelection in 1972). In our new millennium, the 50th anniversary of the international revolutions of 1968 coincided with a farcical repetition of their reactionary aftermath. For many Americans, the pivotal elections of 2016 have become the most blatant symptom, and catalyst, of the West’s downward spiral. Yet, even now, after the deluge of the digital (but still before the deluge of rising seas), interdisciplinary scholars and avant-garde movements alike have yet to take seriously enough the import of Barthes’s post-1968 writings. Unlike his structuralist semiology of the 1960s, Barthes’ late writings offer underexplored models for experimentations with form and medium seeking, firstly, to historicize and learn from political failures, secondly, to deconstruct neoliberal ideology and its cynical discourse’s mediation by cybernetic networks of communication, and, finally, to speculate on alternative strategies for protest and art in a new world order.

In my essay, “Roland Barthes after 1968: Critical Theory in the Reactionary Era of New Media,” published in the Yearbook of Comparative Literature’s volume on Roland Barthes, Return to Mythologies, I reconsider the thinker’s controversial response to the 1960s revolutionary movements. In the process, I trace a theoretical thread from Barthes’ most explicit take on “Mai 1968” in his short piece, “Writing and the Event” (1968), to such indirect meditations on Utopia as his triptych, Sade/Fourier/Loyola (1971).[ii] While my argument expands upon research begun in the earliest years of my doctoral studies,[iii] this article primarily serves to establish a foundation for my future research. I hope this essay will likewise prove of some use for future scholars of counter-cultural movements, avant-garde artists and activists, and critical theorists on the politics of art in the digital age.[iv]

I set the stakes for my argument by exploring Barthes’ shift after 1968 from structuralist to post-structuralist theories and methodologies. To do so, I compare, for instance, his foundational work of cultural semiotics, Mythologies (1957), with his multimodal, non-linear essays in The Empire of Signs (1970). By tracing this oft-acknowledged metamorphosis in Barthes’ writings during the 1970s, I attempt to uncover Barthes’ under-appreciated insights into new media technologies at the intersection points of power (for instance, in his adaptation of cybernetics to analyze the aesthetics of photography in Camera Lucida (1980)). Finally, my essay hones in on Barthes’ last lectures that preceded his untimely death, especially his magisterial collection, The Neutral (1979). In these notational, singular works, Barthes sought to overturn the mystique of his own mastery, adopting his most radically speculative orientation. Exploring territory beyond the paradigms of the traditional sciences and humanities, Barthes experimented with counter-intuitive modes of writing and thinking to negatively outline “neutral” modes of resistance that could bypass, exhaust, or otherwise subvert the inexorable arrogance of power.

After the revolutionary failures of 1968, Barthes sought to unravel the forces of “fascism” wherever he could tease out their seductive traces (not entirely unlike left-over graffiti on a crumbling wall in the aftermath of a failed revolution). Through a baffling process of queering binary hierarchies of thought and affect, I argue, Barthes’ late writings generated invaluable templates, fragmented blueprints for how to live in, and resist, our era’s digital dystopia of polarized politics, algorithmic surveillance, and participatory consumption. By recovering such hidden histories and avant-garde works of power’s theorization in the reactionary age of new media, such emerging fields in the technological humanities as critical digital studies and cultural analytics can find surer footing for nuanced perspectives on the most pressing question of our time. Throughout Barthes’ post-1968 work, especially in such late lectures as How to Live Together (1978) and The Preparation of the Novel (1980), we will discover a sustainable source of inspiration, not only to extend Barthes’ unfinished speculations on innovative models for artistic subversion, but to fortify our communities, and ourselves, as we seek, against all odds, to live in good faith, and to resist our forbidding, forbidden future.

[i] The phrase, “Il est interdit d’interdire,” is freighted with innuendo in the original French. “It is forbidden to forbid” might be its explicit meaning. But “interdire” also gestures toward the specter of censorship, the sovereignty of the Law, and the deviances of self-expression (its Latin roots signifying roughly “between” (inter) “speech” (dire)).

[ii] For further discussion of Barthes’ Sade/Fourier/Loyola as a lyrical meditation on the implications of “Mai 68,” see Tiphaine Samoyault’s Barthes: A Biography (2017).

[iii] I first encountered Roland Barthes’ late lectures during an English graduate seminar, entitled “The Desire to Write,” taught by Wayne Koestenbaum at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. The course featured only three readings: Gertrude Stein’s A Novel of Thank You (1926), Ferdinand de Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet (1935), and Roland Barthes’ Preparation of the Novel (1979). While each became for me a different sort of self-help manual, Barthes’ late lectures most profoundly impacted my perspective on writing, thinking, teaching, and protesting today. I was inspired, in 2014, to co-organize with Claire Sommers a two-day conference at The Graduate Center on Barthes’ late work, entitled The Renaissance of Roland Barthes. In the following year, I edited a collection by the same name (published by The Conversant as a special issue in 2015), bringing into conversation essays by both graduate students (Youna Kwak, Russell Stephens, Claire Raymond, and Margot Note) and pre-eminent critics Rosalind Krauss, Jonathon Culler, Lucy O’Meara, and David Greetham. Without these experiences at the foundation of my doctoral study, and without these wide-ranging thinkers, my current writing on Roland Barthes and the politics of art in the era of new media would never have been possible.

[iv] A genealogy of critical theory on new media extends from such Marxist classics as Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967) to Sofiya Noble’s game-changing Algorithms of Oppression (2018). In the wake of such thinkers as Gilles Deleuze, Julia Kristeva, Jean Baudrillard, and innumerable others, the field of new media studies has evolved into disparate strands, from Peter Starr’s Logics of Failed Revolt: French Theory after May ’68 (1995) to Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan’s essay, “From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Lévi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus” (2011).

Alex Wermer-Colan is a postdoctoral fellow at Temple University’s Scholars Studio. Throughout his creative and critical work as a writer and editor, he has sought to reconsider counter-intuitive approaches to the politics of aesthetics that can bridge the divides between critical theory and cultural analytics, subversive art and political activism. His writing and editorial work has appeared in the L.A. Review of Books, Twentieth-Century Literature, the D.H. Lawrence Review, The Conversant, and Indiana University Press. Read his latest article in the Yearbook of Comparative Literature entitled “Roland Barthes after 1968: Critical Theory in the Reactionary Era of New Media” free for a limited time.

Comments on this entry are closed.