Written by guest blogger, Erin Gallagher-Cohoon.

Between 1946 and 1948, US Public Health Service (USPHS) researchers deliberately exposed Guatemalan prisoners, soldiers, asylum patients, and sex workers to syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid. Leading up to this study, it was discovered that penicillin could cure syphilis and gonorrhea, and researchers were eager to learn whether penicillin had potential as a preventative and not just a cure. The original study design called for a sexual transmission method, although this was quickly supplanted by medical exposures. To put it more bluntly, the original study design called for hiring sex workers (who had either tested positive or were simply assumed to be infected with a venereal disease) to have sex with prisoners and soldiers and thus, it was hoped, to transmit venereal diseases from the women to the men. It was politically inadvisable in the United States for government researchers to be hiring sex workers. So they headed to a country with legalized prostitution, Guatemala.

In 2015, in the midst of my research on the USPHS’ Sexually Transmitted Disease Inoculation Study, I came across a part of the history that made no sense to me.

At this point in my studies, the records of the lead medical researcher, Dr. John C. Cutler, had been redacted and digitized (see https://www.archives.gov/research/health/cdc-cutler-records). So, I imagine I was squinting at my laptop in confusion.

National Archives and Records Administration

National Archives and Records Administration

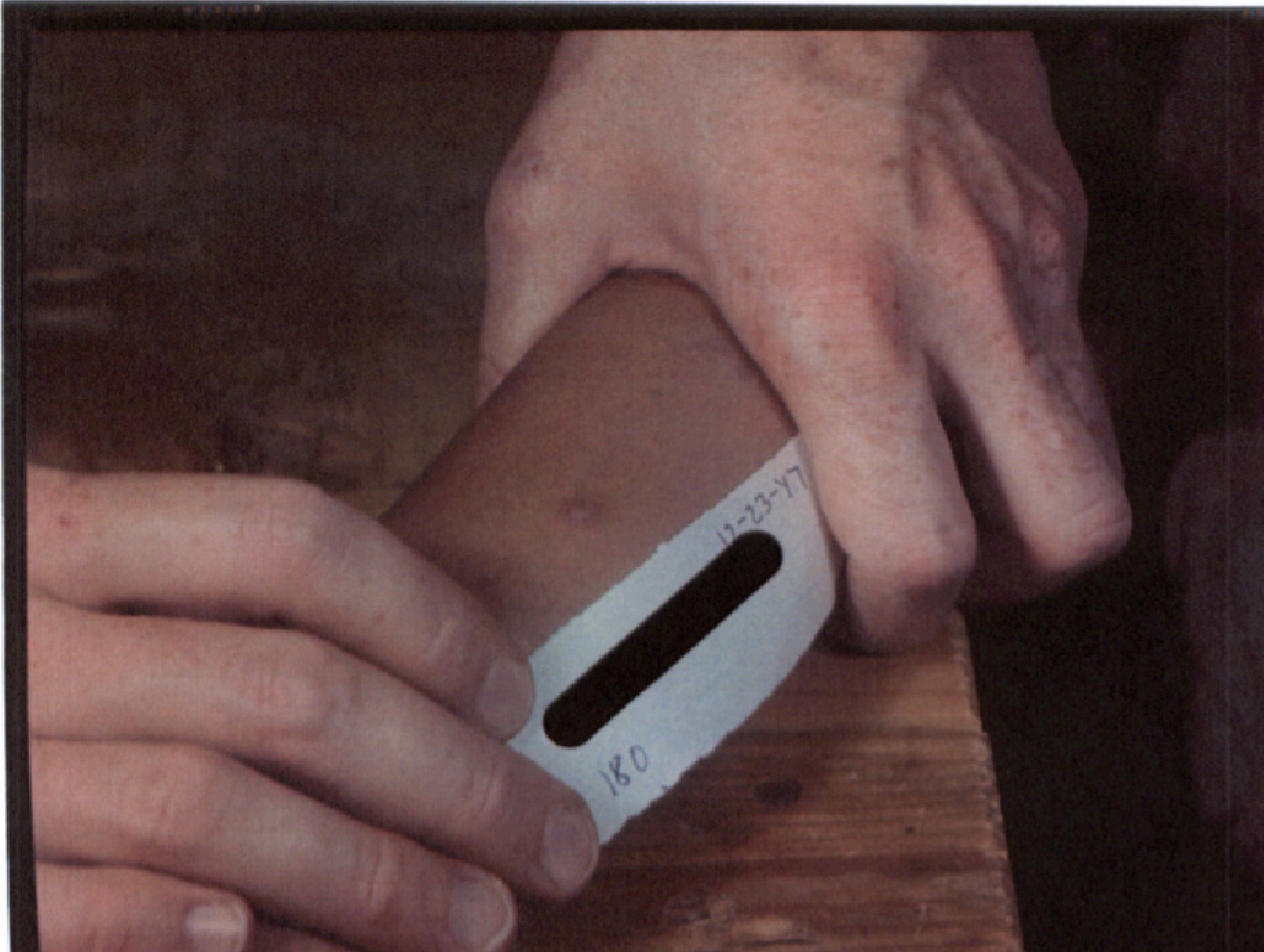

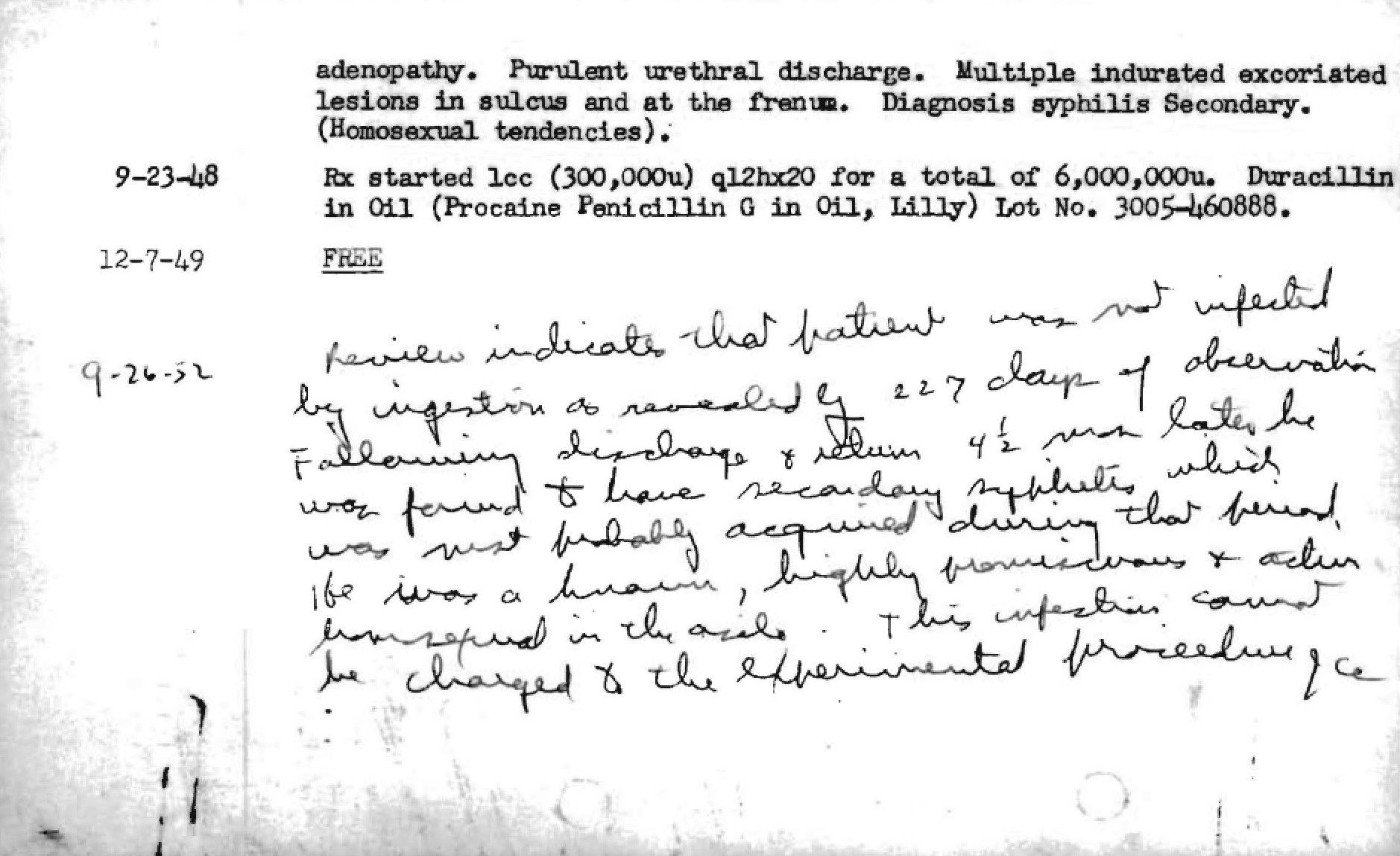

I was reading the patient index cards. Patient 147, a male asylum patient, “was a known, highly promiscuous and active homosexual.”[1] He was not the only male subject whose index card included a reference to same-sex sexual activities.

These homosexual encounters were significant to me because they contradicted Dr. Cutler’s own words. In his “Final Syphilis Report,” he wrote: “homosexual contacts did not significantly alter experimental results.”[2]

National Archives and Records Administration

National Archives and Records Administration

How, I wondered, could Dr. Cutler so readily dismiss the possibility that homosexual contacts might have been experimentally significant? On one hand, it seemed to me, he was dismissing the same-sex sexual activity of his male research subjects; while on the other, he was recording the existence of these “contacts,” and later archiving them for future researchers to find.

The easy answer is that these encounters, based on his records, were statistically rare, and that “no clinical evidence of spread of syphilis by this route was observed.”[3] As I argue in my recent article in the Canadian Bulletin of Medical History, however, this does not sufficiently explain the contradictions within the records. Rather, as the original study design shows, the study was based on a flawed understanding of disease transmission that assumed the presence of an infected female body, an assumption that was fundamentally heteronormative. Within this context, homosexual behaviour was implausible or, at best, irrelevant.

[1] Patient 147, Index Cards, Insane Asylum Female Patients Con’t, Hollinger Box 1a, CDC Record Group 442, Records of Dr. John C. Cutler, National Archives and Records Administration at Atlanta. Although grouped with the index cards of ‘Insane Asylum Female Patients Con’t,’ this patient was in fact male. On 19 September 1947, it was noted that “Penis-papule at right of frenum, 3×5 mm. The frenum and foreskin surrounding papule are indurated.”

[2] Records of Dr. John C. Cutler, Final Syphilis Report, Folder 1, 29.

[3] Records of Dr. John C. Cutler, Final Syphilis Report, Folder 1, 27.

Erin Gallagher-Cohoon (Department of History, Queen’s University) recently published “Despite Being ‘Known, Highly Promiscuous and Active’: Presumed Heterosexuality in the USPHS’s STD Inoculation Study, 1946–48” in the Fall 2018 issue of Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. The article is free to read for a limited time here.

Comments on this entry are closed.