Written by guest blogger, Katherine Turner.

I first became aware of Mary Anne Clarke when I was asked to edit a group of scandalous memoirs by 18th-century and Regency women (Women’s Court and Society Memoirs, published in 2010 by Pickering and Chatto, now Routledge). Although writing the voluminous footnotes proved to be a grim task, I became fascinated by how these women mixed up the popular genres of memoir, scandal narrative and political satire to vindicate themselves to a reading public hungry for tales of misbehavior in high places. One of the texts I edited was The Rival Princes, an exposé published in 1810 by the courtesan Mary Anne Clarke of her role in a national scandal which had almost brought down the government in 1809 when it was revealed that she had used her adulterous relationship with the Duke of York to acquire promotions for cronies of hers in the army, the church, the East India Company, and even the House of Commons. When the scandal broke, Clarke was the star witness in a protracted Parliamentary trial which was reported in gleeful detail in the newspapers. The case also inspired many satirical cartoons which reached every corner of Britain, their saucy images of the Duke of York and his mistress in bed together doing yet further damage to the shaky reputation of the British royal family. Many of the cartoons, some by the Regency’s finest satirical artists such as Cruikshank and Rowlandson, can be viewed via the British Museum‘s excellent website; simply search the collections (for ‘images only’) using the term “Mary Anne Clarke,” and a whopping 189 items appear. (The British Museum’s copyright regulations prohibit electronic transmission, so alas I am unable to reproduce them here.)

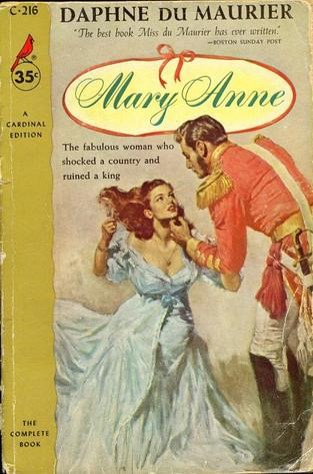

In tandem with my historical research into the scandal, I soon discovered that Clarke was the great-great-grandmother of Daphne du Maurier, and that in 1954 du Maurier published a fictionalized biography of Clarke, entitled Mary Anne. Happy to have an excuse to escape from historical footnotes, I indulged myself for a few months by reading through most of du Maurier’s fictional oeuvre. Like many of du Maurier’s readers, I was drawn in by her tight plotting, evocative sense of place, and complex (even villainous) female characters, and by the subtexts of feminist indignation which run through many of her novels. Virago have recently reissued many of the novels with pithy introductions by contemporary women writers and critics, and if you don’t know them already, then I urge you to rush out right now and get copies. They make excellent reading for the holiday season, whether you’re in search of tense psychological drama (Rebecca, My Cousin Rachel) or more bodice-ripping historical yarns (Jamaica Inn).

Mary Anne, as my recent article in UTQ observes, is a bit of an anomaly for du Maurier; since it was grounded in so much historical reality, du Maurier had less imaginative freedom than when writing her other works, and she clearly found the translation of her historical ancestor into a novelistic character to be quite a challenge. But in many ways this is one of her greatest achievements; not only does du Maurier bring to life a complex and colorful period in English history, which captured the public imagination in ways similar to cases such as the OJ Simpson trial or the Clinton impeachment; she also uses the novel to meditate upon her own literary ancestry, and to trace her own creative energies back to this indomitable woman. Mary Anne Clarke comes across as both heroine and victim, and the way in which she exposes the powerful men who exploited and ultimately abandoned her continues to resonate today.

Katherine Turner‘s article “Daphne du Maurier’s Mary Anne: Rewriting the Regency Romance as Feminist History” can be found in the latest issue of University of Toronto Quarterly. Read it online here: http://bit.ly/utq864.

Comments on this entry are closed.