Written by guest blogger, Justin Rogers-Cooper.

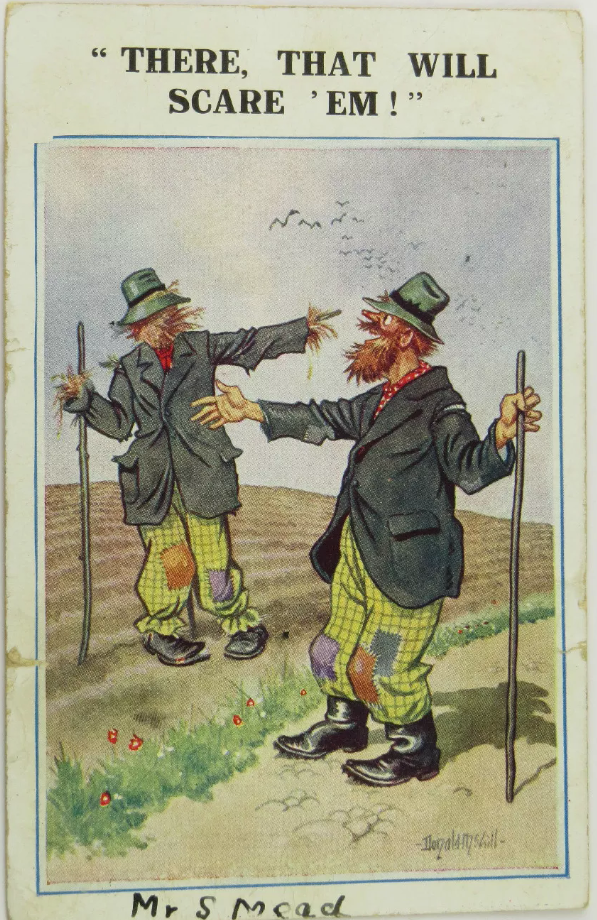

Sometime last year I slipped a postcard of a “tramp” (as pictured in the right-hand image) into a UV-protected plastic sleeve. Then I put it into a neat pile of similarly sleeved postcards. I carefully placed them into a black museum storage box, and stacked that box atop a similar one. This other one was full of “Coxey’s Army” marginalia – stuff about the 1894 march on Washington by unemployed men.

I couldn’t help but remember being a kid in North Carolina slipping baseball cards of Mark McGwire, my favorite player, into hard plastic cases. I’m glad I’m not preserving butterflies in glass boxes, but when I stare up at the many clamshell storage boxes that tower above my cramped library in Brooklyn, it’s pointless to deny I suffer from obsessive instincts.

The boxes in fact supplement the subject that sparked the acquisitive fever: the 1877 General Strike. I blame that strike for the eBay push notifications that arrive like news headlines on my iPhone. It was one of those stories that completely blew my mind, and I quickly put down everything else once I realized it had only been half-told.

I actually only learned about the strike five years ago, while finishing my Ph.D in English. I was struck by how I could have missed something so large. In July 1877, hundreds of thousands of people joined a trainmen strike for higher wages, including other industrial workers, in a multicultural coalition of women, children, and families, many of them immigrants – in addition to thousands of unemployed, unskilled, unwaged, and migrant workers. It was an event with many centers (Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Chicago, St. Louis) and also full of contradictions (both interracial cooperation and racist violence).

It’s an event so complex it’s sometimes hard to see all at once. I first encountered the strike as an English person, but trying to understand it transformed me into something else: an “American studies” person.

On the plus side, the fever sent me scurrying online and traveling to libraries, archives, and historical societies, where I found and collected artifacts that propelled my research. One text in the Columbia rare books library, The Commune in 1880, was so deliciously weird, and had such tremendous explanatory power, that it became the focus of my article, “Downfall of the Republic! The 1877 General Strike and the Fictions of Red Scare,” recently published in the Canadian Review of American Studies (Volume 46 Issue 3).

Perhaps the only thing more bizarre than The Commune in 1880, in fact, might be the dozens of tramp postcards I’ve assembled. They testify to one of the General Strike’s other elements: the army of migrant men, then called “tramps,” who participated in the strike. Papers labeled them and the rioters “communists,” but over time they helped inspire any number of characters and caricatures in global pop culture for decades to come, from Charlie Chaplin’s tramp to the Sunday comic strip “Pete the Tramp,” not to mention Coxey’s Army.

Oh, if you’ve never heard of “Pete the Tramp,” feel free to drop by. I have a box to show you.

To read more on the 1877 General Strike, be sure to check out Justin Rogers-Cooper’s full article, “Downfall of the Republic! The 1877 General Strike and the Fictions of Red Scare”, published in the latest issue (Volume 46 Issue 3) of the Canadian Review of American Studies!

You can follow Rogers-Cooper on Twitter @nycjrc

Comments on this entry are closed.