Written by guest blogger, Patrick Lacroix

Immigration and immigrant integration made a sudden and unexpected eruption into Canada’s federal election in 2015. The Conservative Party was determined to prevent Muslim women from wearing the niqab at citizenship ceremonies. The New Democratic Party’s commitment to civic nationalism and its openness on this issue may have cost it valuable votes. The “niqab issue” set the NDP apart from the Conservative and Liberal parties and seemed to contribute to its rapid fall from grace in Quebec.

In a recent contribution to the Canadian Journal of History, I study some of the antecedents to the place of immigration policy in Canada’s current partisan debates. This interest stems from my major research paper as a graduate at Brock University in 2009-2010. I was then studying the Catholic Church’s approach to minority rights in post-war Canada, a project that demanded attention to political parties’ and religious stakeholders’ views of immigration policy.

Early on, I was struck by the richness of the literature on the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (the CCF, the predecessor to today’s NDP), especially its advocacy of human rights. But few scholars have studied the party’s approach to immigration, something I found puzzling. Ever curious, I went back to the sources—the party’s founding documents, official newspaper, manifestos, and campaign platforms. Scholars’ silence began to make sense: the party itself had sometimes been wholly silent on immigration policy. This was, I suggest, a calculated silence that reflected divisions within the party and commitments to contradictory principles.

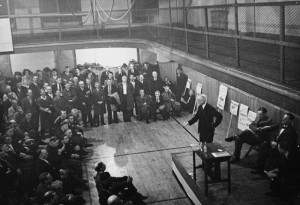

Library and Archives Canada. MIKAN no. 3193170 Title: J.S. Woodsworth at work.

Library and Archives Canada. MIKAN no. 3193170 Title: J.S. Woodsworth at work.

The founders and early leaders of the CCF were staunch allies of the labour movement. They opposed any vast influx of people—especially those seen as racially subaltern—as a way of protecting “old-stock” Canadians’ working conditions. Yet many of the same leaders embraced a universalism influenced by socialist theory and, paradoxically perhaps, the Social Gospel.

These contradictions forced difficult debates upon the CCF during the Depression, but its future tack became apparent as it pressed the Canadian government of Mackenzie King to accept Jewish refugees from Europe on the eve of World War II. Following the war, the party called for an end to ethnic and racial discrimination in admissions to Canada. It remained committed to economic nationalism—with its attendant protection of Canadian workers—but now embraced a civic nationalism that became most evident in its human rights advocacy.

I hope that my CJH article and some of our more recent political developments will spur scholars to further investigate the place of immigration policy in the history of Canadian partisan politics.

A graduate of Bishop’s University and Brock University, Patrick Lacroix is now a Ph.D. candidate at the University of New Hampshire. His dissertation reconsiders the intersection of faith and politics in the United States under John F. Kennedy.

Patrick Lacroix’s article, “From Strangers to “Humanity First”: Canadian Social Democracy and Immigration Policy, 1932–1961” is available in the Canadian Journal of History/Annales canadiennes d’histoire Vol. 51 Issue 1. Read it at CJH Online or on Project MUSE.

Comments on this entry are closed.