Despite the “gloom-and-doom” forecasts for the end of the printed word, newspapers continue to persist in the present day. One only has to look up from the subway floor to see people devouring the printed word every morning, reading everything from the Metro News to the Toronto Star. Just as Mrs. Moodie is recorded saying in 1852, “The Canadian cannot get on without his newspaper,” the same can be said of today’s morning transit commute (Talman 166).

Despite the “gloom-and-doom” forecasts for the end of the printed word, newspapers continue to persist in the present day. One only has to look up from the subway floor to see people devouring the printed word every morning, reading everything from the Metro News to the Toronto Star. Just as Mrs. Moodie is recorded saying in 1852, “The Canadian cannot get on without his newspaper,” the same can be said of today’s morning transit commute (Talman 166).

However, newspapers were not always focused on the latest scandal involving crudely-spoken mayors or irresponsible celebrities, nor were they riddled with accounts of sporting events. Instead of a complete dedication to local news, the newspapers of Canada West in the 1840s and 50s were proportionally inclined to save space for literature, specifically selections taken from the work of those considered to be the best authors of the time. James J. Talman, in his article “Three Scottish-Canadian Newspaper Editor poets,” suggests that these literary inclusions undoubtedly raised the cultural standards of these newspapers’ communities and nurtured, in small part, a rise in Canadian culture.

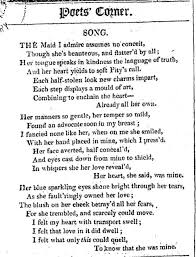

Talman focuses on three Scottish-Canadian editors who were also poets. While these editors were not exceptionally talented, especially in the terms of today’s poetry, they were well-respected by their surrounding communities where their work flourished. George Menzies, the editor of the Woodstock Herald, and his poetry while often morbid also tastefully encapsulated his town, such as his feeble poem titled “Woodstock in 1854,” in which he describes his town in rhyme: “a simple, quiet village stood,/ Surrounded by the then remaining wood” (169). The second editor/poet was Robert Jackson Macgeorge of the Streetsville Weekly Review. As the editor, he published literary references and poems tailored for the housewife and farmer. He also included his own poetry, where he wedded Scotland and Canada together in addition to being deeply infused with religious conviction (he was also a church dignitary). Finally, Thomas Macqueen, editor of Goderich‘s Huron Signal, had high literary ambitions for Canada, seen by his printed editorial, “Will nobody write a few songs for Canada?” (176). In addition to a call for literary talent, Macqueen also printed poetry he had written. One of his poems, “Our Own Broad Lake,” celebrates the beauty of Lake Huron: “To tell of Huron’s awful grandeur; /Her smooth and moonlight slumbering” (176).

Alas, even Macqueen admitted in the 1800s that newspapers and their editors were “creatures of reality” and thrived “by the quantity of hard cash”; therefore, the “delicate ditties” of poets were unable to find the solid niche within the newspaper that Macqueen had initially hoped for (175). But despite this bleak view, Macqueen and the other two Scottish editors mentioned here obviously felt a need to awaken Canada to its own poetic potential, and their individual newspapers set out with the objective of “improving the tone of thought and action in a prosperous community, [and] establish[ing] a local Newspaper under the management of a man who [would] fearlessly bring the filth to the bottom” (176)

These Scottish-Canadian newspapers were clearly not the only impetus for creating a native culture in Canada, but in a period when one had scarcely developed, they certainly lent a hand, a conclusion that Talmer alludes to. Perhaps it is also about time that today’s newspapers brought the filth to the bottom and returned to the imaginative that once fostered Canadian creativity and culture. Something to ponder…

Interested in reading more about Canadian newspapers before the subsuming love for public shaming and disaster? Consider purchasing a more in-depth look at Talmer’s article “Three Scottish-Canadian Newspaper Editor Poets,” published in the Canadian Historical Review in 1947 or purchasing a subscription to gain access to all of the journal’s fascinating historical content.

Comments on this entry are closed.