Written by guest bloggers, Odinn Melsted and Irene Pallua.

Since the mid twentieth century, oil and natural gas – in short: hydrocarbons – have been the dominant energy carriers in industrialized countries. They have been the main energy providers for cars, trucks, ships, airplanes, industries and home heating. What is often overlooked is that the rise of hydrocarbons meant the decline of coal. At the midpoint of the twentieth century, coal was still the fuel of choice in railroad and maritime transportation, for industrial production, in residential heating, as well as electricity production. Yet between the 1940s and 1970s, a relatively short period of time in energy history, coal was largely pushed aside by hydrocarbon alternatives. Recent research on historical transitions and today’s practical experiences in attempting to implement a renewable energy transition have, however, revealed that incumbent energy systems tend to be resistant to change. How, then, could hydrocarbons take over so quickly?

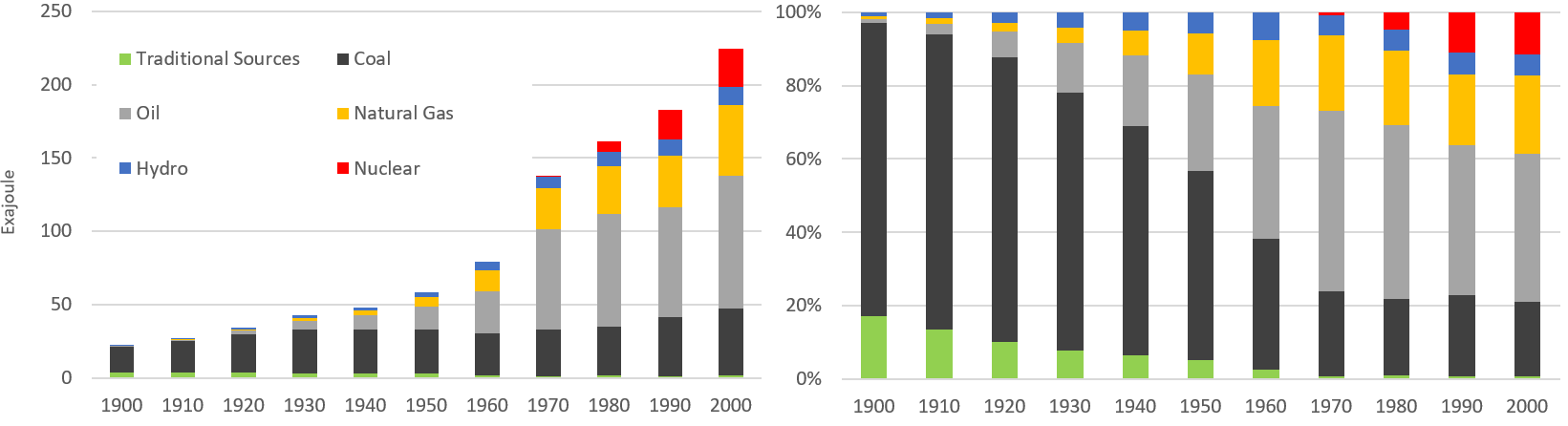

Total Primary Energy Supply (TPES) in the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) area. Own figure based on data from Arnulf Grübler, “Energy Transitions,” in: Cutler Cleveland, ed. Encyclopedia of Earth (Washington, D.C.: National Council for Science and the Environment, 2008.

One of the main challenges when dealing with energy history is to assess the scale of a transition. One way of doing so is to take a look at historical energy data. The figures above show Total Primary Energy Supply (TPES) in OECD countries from 1900 to 2000 for different energy carriers. The graph on the left depicts the absolute values of energy carriers in exajoules. Here we can see that oil and natural gas multiplied between 1940 and 1970, accounting for much of the simultaneous increase in overall energy supply. In addition, we can identify a diversification from coal to multiple fuels. On the right, the figure shows the same data as relative shares, which reveals that coal lost its dominance in the energy mix as hydrocarbons took over. By looking at both absolute values and relative shares, we can see that coal clearly lost its dominant position to hydrocarbons, but at the same time maintained a status quo; its total supply only decreased slightly at first and then actually increased in the long run. How can this contradiction be explained? In what context did hydrocarbons replace coal, and what accounts for the continuing importance of coal in the energy mix?

Those are some of the questions we deal with in our article entitled “The Historical Transition from Coal to Hydrocarbons: Previous Explanations and the Need for an Integrative Perspective”, which appears in the Canadian Journal of History’s special issue on the Material Realities of Energy Histories. We are currently both PhD candidates at the University of Innsbruck, Austria, and have been working on dissertation projects on the history of energy. As we both focus on continuities and changes in the use of different energy carriers in the second half of the twentieth century (Odinn Melsted on Iceland’s energy system and Irene Pallua on the Swiss heating sector), we have been faced with the challenge of explaining how and why the transition from coal to hydrocarbons took place so quickly in so many different parts of the industrialized world. We each discovered that the existing literature on energy history only marginally deals with the question of why hydrocarbons replaced coal. All too often, oil and natural gas are portrayed as the superior fuels that were bound to take over from coal inevitably. When diving deeper into the vast literature on coal, oil and natural gas, the changes in energy supply systems, evolution of industries, transportation and heating, however, we discovered that many causal explanations have already been provided. Yet the disparity of the literature has made it difficult to grasp them and see them in the context of the over-arching transition from coal to hydrocarbons.

Coal was long the fuel of choice for steam locomotives, industrial production and residential heating, but largely replaced with hydrocarbons in the mid twentieth century. This was due to a variety of causes, ranging from competitive prices and policy to limit smoke pollution, to the physical advantages of hydrocarbons, which are lighter, cleaner, have a higher energy density and are easier to control in combustion than coal. Pictures: Wikimedia Commons.

In the article, we draw together the causal explanations for the transition from coal to hydrocarbons. One of the problems we discovered in the research process is that the literature presents a gap between two perspectives: one on energy “supply” and another on “consumption.” The supply perspective focuses on the diversification of the overall energy supply system, where oil and natural gas were introduced to formerly coal-dominated energy economies. The consumption perspective, on the other hand, focuses on how consumers in different areas of the energy economy decided to switch from coal to hydrocarbon alternatives.

We therefore integrated these perspectives and conceptualized the shift from coal to hydrocarbons as a complex transition that occurred at two levels. On the one hand, hydrocarbons became available as alternatives to coal at the level of energy supply, which created favourable circumstances for energy consumers to shift to hydrocarbons. On the other hand, individual energy consumers in railway and maritime transportation, residential heating, industrial production, and electricity generation actively decided to use hydrocarbon alternatives as substitutions for coal. By revisiting the explanations of the rising use of hydrocarbon energies in the mid twentieth century, we hope to direct attention to this hitherto understudied, yet nonetheless decisive transition in energy history and present an innovative approach to the analysis of historical fuel transitions.

Odinn Melsted is the recipient of a DOC-fellowship of the Austrian Academy of the Sciences at the Department of History and European Ethnology at University of Innsbruck. His doctoral project deals with Iceland’s low-carbon transition during 1940–1990 and has also been supported by the Landsvirkjun Energy Research Fund.

Irene Pallua is a PhD candidate at the Department of History and European Ethnology at University of Innsbruck. Her main research interest is in history of energy at the juncture of technology, society, and the environment. She is currently working on her PhD project on the history of heating in Swiss households.

Read their article in the latest issue of CJH, “The Historical Transition from Coal to Hydrocarbons: Previous Explanations and the Need for an Integrative Perspective”—free for a limited time here.

{ 1 trackback }

Comments on this entry are closed.