Written by guest blogger, Patrick Lacroix.

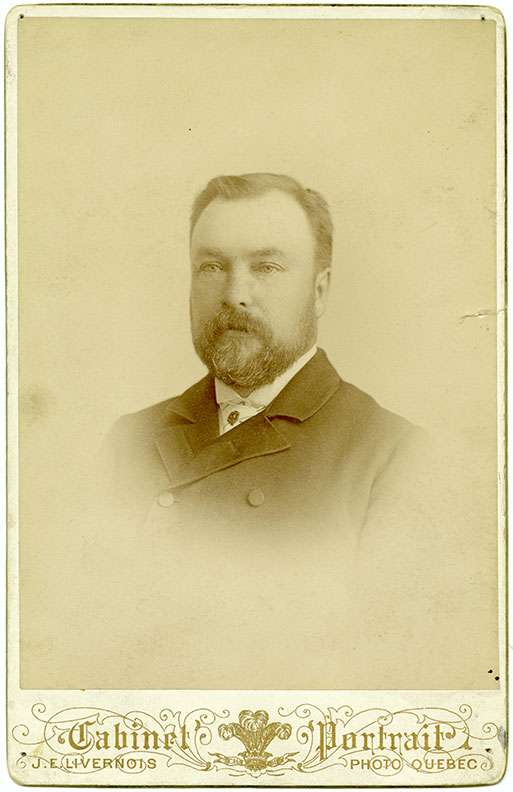

Louis-Prosper Bender. Photograph by J.E. Livernois (c. 1880)

Louis-Prosper Bender. Photograph by J.E. Livernois (c. 1880)

Everything about Prosper Bender (1844-1917) seemed to suggest that he would be noticed and remembered—everything down to his name. He left a life of comfort to serve as a physician in the U.S. Army in the final year of the Civil War. He bucked the Canadian Medical Association by practicing homeopathy. He made his home the centre of Quebec’s literary life in the 1870s. He sought to bridge Canada’s two dominant cultures when few others could or would.

Bender did all of this in the span of two decades—and then left. Indeed, the most interesting part of his life may be his abrupt move to Boston in the 1880s, a decision that undermined his burgeoning fame as a Canadian littérateur and helps to explain why he has vanished from our historical consciousness. At the same time, the move highlights a constancy of principles that might otherwise go unnoticed.

Had he remained in Quebec City, Bender might have earned great fame as a writer; the works he penned and published presaged as much. But, in 1882, he began a transnational journey that would last some twenty-five years. Personal reasons for the move are easily found. He failed to make the first slate of members of the Royal Society of Canada, while Boston was home to a thriving literary and artistic scene and seemed to promise new professional opportunities.

In retrospect, it is Bender’s politics that stand out most. Interethnic suspicions, graft, and a languishing economy had turned Canada into a sick nation, Bender argued through most of the 1880s. Confederation had not yielded its expected fruit. Awed by American industrial power and the spirit of republican values, the expatriate began to plead for Canada’s annexation by its mighty neighbour.

Bender nevertheless remained true to his principles and to his own bicultural heritage. He continued to promote a better understanding of French-Canadian society and culture—on both sides of the border—among their English-speaking neighbours. He defied the nativism that afflicted budding Franco-American communities and the angry rhetoric that sprang in the era of the Riel controversy. Adroitly, he crossed cultures and borders without succumbing to the more profitable tide of prejudice.

As our own times show, fear mongering and scapegoating easily drown out voices of moderation and understanding. When Bender died in early 1917, his home country was about to experience animosities not seen since 1885; little came of his efforts. That too may explain, despite the numerous columns he penned in Quebec newspapers after he returned to the province, the obscurity that awaited him.

Bender’s life sheds light on the possibilities of Canadian and French-Canadian nationhood in the late nineteenth century. But we stand to gain more by remembering his work as an intercultural broker, who may yet inspire those who would counter the “[f]anatics [who] have always been numerous enough . . . to supply subjects for quarrels, as well as disputants at short notice, to the danger of the public peace.”

Learn more about Bender, the literary scene of his time, and his work as a mediator of cultures in the latest issue of the Journal of Canadian Studies (52.2).

Patrick Lacroix, Ph.D. is an instructor at Phillips Exeter Academy (Exeter, N.H.). His article “Seeking an ‘Entente Cordiale’: Prosper Bender, French Canada, and Intercultural Brokership in the Nineteenth Century” is free to read for a limited time in the latest issue of the Journal of Canadian Studies. Click here to read it online.

Comments on this entry are closed.