Written by guest blogger, Giacomo Sanfilippo.

Wendy VanderWal-Gritter’s Generous Spaciousness: Responding to Gay Christians in the Church, which I was asked to review for the upcoming issue of the Toronto Journal of Theology (Volume 33, Issue 1), serves an important “pre-theological” purpose. She has written not a work of theology per se—as she herself acknowledges—but the raw material from real human lives out of which a living theology can take shape over against a lifeless casuistry.

She frames her book as an appeal to the leadership and laity of traditional and conservative churches to open their hearts to the testimony of Christian men, women, youths, and children who experience their attraction to their own gender as a natural, inalienable aspect of their God-given selves.

It comes as a surprise to my colleagues when I mention that the modern world’s first Christian theology of same-sex love appeared in Moscow in 1914.

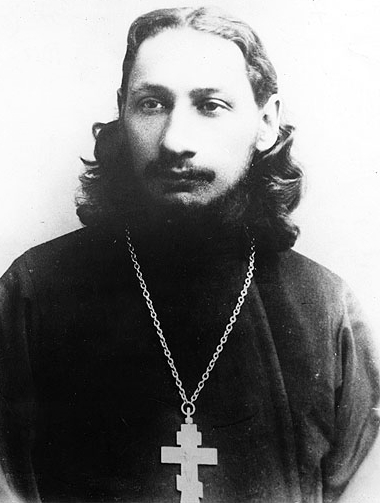

Pavel Florensky, a young married priest, father of his first child, and now widely acclaimed as one of the 20th century’s foremost Orthodox theologians, dedicated The Pillar and Ground of the Truth: An Essay in Orthodox Theodicy in Twelve Letters to the memory of his beloved Sergei Troitsky, his fellow seminarian and roommate at the Moscow Theological Academy. The two had planned to spend the rest of their life united in a “friendship” analogous to marriage in nearly every respect but procreation, including the natural need to actualize their spiritual union through some form of bodily expression.

The unusual emblem selected by Florensky himself for the frontispiece, his achingly reminiscent dedication in “Letter One: Two Worlds,” and the oft reiterated terms of endearment with which he addresses Sergei through the successive topics of his book all culminate in an explicit theological exposition of their love in “Letter Eleven: Friendship.” For this chapter Florensky chose an emblem that depicts two naked male cupids playfully shooting at each other with their bows and arrows, one throwing his arms up in a gesture of laughing surrender to the other. (Boris Jakim’s translation preserves the original artwork.)

Here I introduce publicly, for the first time, a term of my own invention: conjugal friendship as a theological substitute for “same-sex union.”

Here I introduce publicly, for the first time, a term of my own invention: conjugal friendship as a theological substitute for “same-sex union.” It follows Florensky’s lead in foregrounding the subsumption of eros in philia—for philein means not only to love, but to kiss—and the close analogy between monogamous marriage and exclusive friendship. Etymologically, the Latin conjugalis and its Greek equivalent syzygos have less to do with the sexual or procreative nature of a relationship and more with its foundation in a spiritual “co-yoking” (see Phil 4:3).

An Orthodox theology and spirituality of same-sex love, consistent with our ascetical vision of ecclesial life as a process of deification through the synergistic action of divine grace and human effort, can only begin to emerge when we shift our focus from a near voyeuristic obsession with the possible range of techniques of sexual performance to the spiritually and emotionally unitive nature of love between two men or two women. A full century before VanderWal-Gritter’s appeal, Father Florensky showed the way forward for churches that self-identify as traditional.

Giacomo Sanfilippo is a member of the Orthodox Church and a PhD student in Theological Studies at Trinity College. He has a primary research interest in questions of sexual and gender diversity in human and ecclesial life.

His review of Wendy VanderWal-Gritter’s Generous Spaciousness: Responding to Gay Christians in the Church will appear in the upcoming Spring 2017 issue (Volume 33, Issue 1) of the Toronto Journal of Theology!

Comments on this entry are closed.