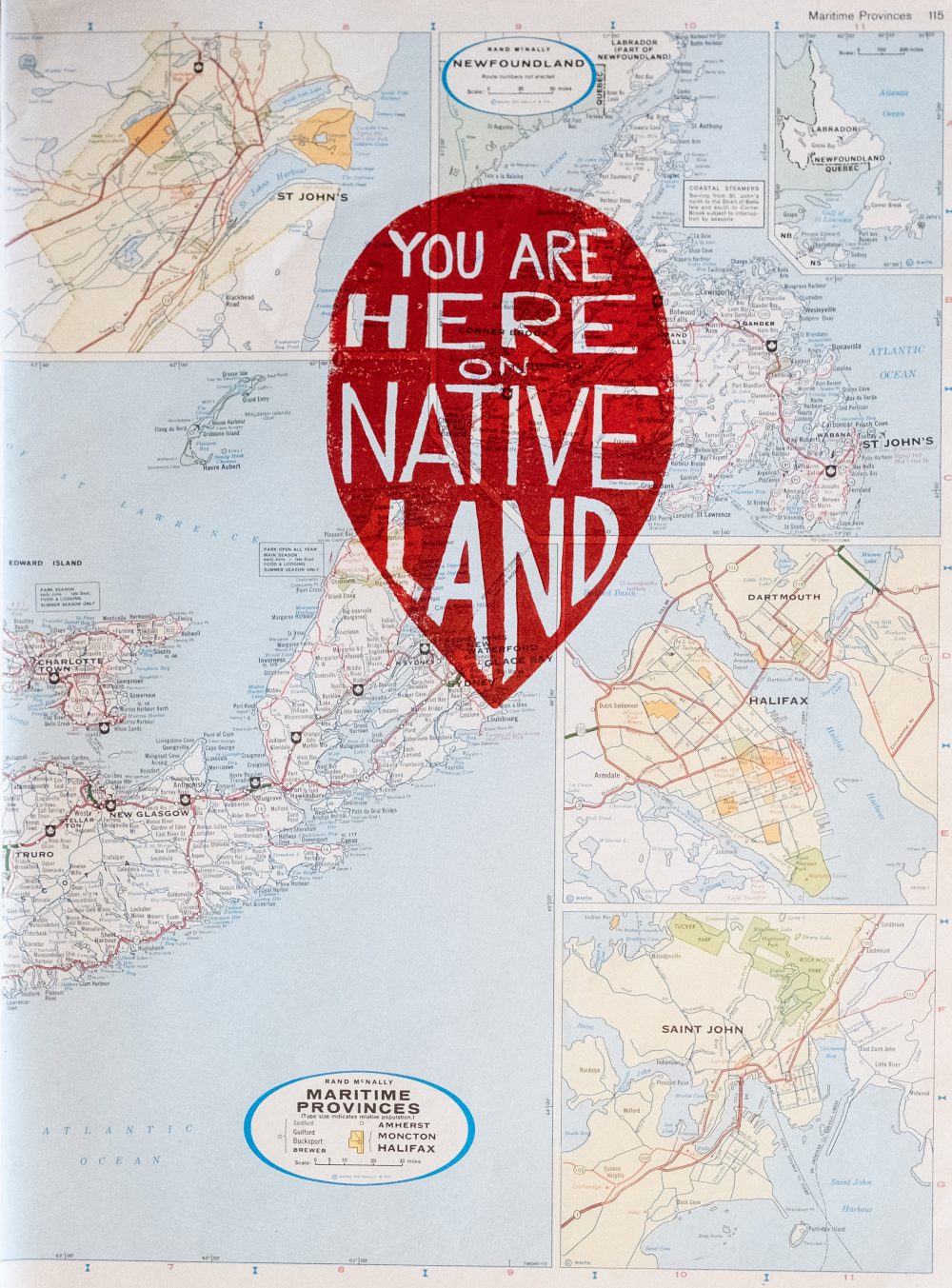

Print by Katrina Brown Akootchook and photograph of the print by Berdell Paninguna Akootchook. Used with permission.

Written by guest blogger Reuben Rose-Redwood.

Mapping is an art of persuasion that often aims to seduce us into believing that the map merely describes the world as it is, yet historians of cartography have long understood that mapping is a form of world-making. When European colonial explorers mapped the world at the behest of imperial monarchs, the names of places and boundary lines that they inscribed on maps were instrumental in creating the geographical imaginaries of empire. These acts of colonial world-making were also acts of world-taking – placing the imaginative geographies of Indigenous peoples under erasure and ultimately resulting in the dispossession of Indigenous lands to make way for colonial settlement and territorial control.

This Eurocentric legacy of colonial mapping continues to shape geographical imaginaries in the present, and there is no shortage of both conventional and critical historical accounts of the “imperial map.” Yet, by continuously highlighting the power of colonial and imperial maps, this has the effect of reinforcing a Eurocentric narrative of cartographic history that further marginalizes Indigenous traditions of mapping. Yet how might we move beyond the colonial cartographic frame in an effort to decolonize the map?

In a recent special issue on “Decolonizing the Map” in the journal, Cartographica, which I co-edited with Natchee Blu Barnd, Annita Hetoevėhotohke’e Lucchesi, Sharon Dias, and Wil Patrick, we contend that recentering Indigenous mappings is a necessary step toward decolonizing both cartographic theory and practice as well as the stories we tell about the history of cartography. Indigenous and decolonial mapping can take many different forms, from the reclamation of Indigenous place names to the mapping of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

As we began reflecting on the contributions to the special issue of Cartographica that we guest edited, it became clear to us that decolonial mapping is not only about Indigenizing the content of maps but also involves decolonizing the protocols and values that inform the map-making process itself. As one of the co-editors of our special issue, Annita Hetoevėhotohke’e Lucchesi, put it in a recent interview, “The form is only one small part of what makes a map Indigenous – the values and practices underpinning and influencing the form are the big stuff.”

In contrast to the masculinist legacy of Western cartography, many of the leading scholars and practitioners who have contributed to Indigenous cartography are women, including Indigenous cartographers such as Margaret Pearce, Renee Pualani Louis, and Annita Hetoevėhotohke’e Lucchesi, among others. For non-Indigenous scholars, such as myself, I believe we have a responsibility to not only acknowledge our privileges but to decenter the arrogance of our own “expertise” in order to make space for Indigenous voices in our disciplines and beyond. If mapping is a form of world-making, Indigenous cartographers will surely lead the way in charting a course toward the place-worlds of a decolonial future.

Reuben Rose-Redwood is a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Victoria. His research focuses on cultural landscape studies, critical toponymies, the politics of mapping, and the history of geographical thought, among other topics. He has edited a number of books, including The Political Life of Urban Streetscapes: Naming, Politics, and Place (2018), and is Managing Editor of Dialogues in Human Geography. He is currently conducting research on controversies over statues, monuments, and place names on university campuses.

Most recently, he has served as lead editor of a special issue of Cartographica on “Decolonizing the Map.”

The UTP Journals blog features guest posts from our authors. The opinions expressed in these posts may not necessarily represent those of UTP Journals and their clients.

To continue with the University Press Blog Week Tour, visit the posts at other contributing presses.

Amherst College Press

Bristol University Press

Bucknell University

Duke University Press

Georgetown University Press

Johns Hopkins University Press

Penn State University Press

Temple University Press

UBC Press

University of Illinois Press

University of Manitoba Press

University of Toronto Press

Wilfrid Laurier University Press

Comments on this entry are closed.