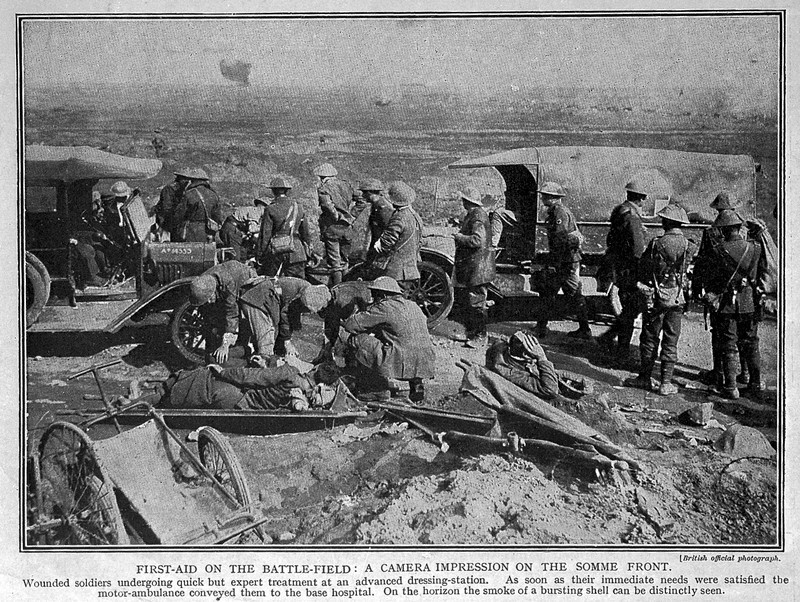

Image Credit: World War One: first aid on the battlefield, Somme. Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Written by guest blogger Dr. Simon Harold Walker.

In 1916, just weeks after the first battle of the Somme, a Scottish Private penned his suicide note. The note began, ‘I cannot stand it anymore…they will not let me come home.’ This desperate Private was not the only man to take his own life during the First World War. In fact, it is increasingly becoming apparent that this was not an entirely rare event. Another, a former driver in the Royal Army Medical Corps, wounded out of service in 1916, also took his own life after being refused for reenlistment. Potentially influenced by the rhetoric of the white feather campaign, and shame and emasculation directed at those not in service, he lay down on a train track in 1917 to be decapitated.

Suicide within the British Military is a long-standing issue and topical issue. For the Scottish Armed Forces, recognition and support for these cases have been a long-term struggle. To this day, the charter from 1923 which outlines who is entitled to be named on the Honour Roll, explicitly forbids the inclusion of suicide cases:

A member of the Armed Forces of the Crown or of the Merchant Navy who was either a Scotsman (i.e. born in Scotland or who had a Scottish born father or Mother) or served in a Scottish Regiment and was killed or died (except as a result of suicide) as a result of a wound, injury or disease sustained (a) in a theatre of operations for which a medal has been or is awarded; or (b) whilst on duty in aid of the Civil Power.

Yet, Scotland has also been at the vanguard of dealing with military mental health in recent history. The infamous Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh developed increasingly sophisticated and innovative ways to treat and understand Shellshock during and after the First World War. Initially, a hydropathic institute specializing in water therapy; as an understanding of Shellshock developed, practical recovery techniques for psychiatric first aid were introduced for patients which included: swimming, golf, tennis, and cricket. Patients made model yachts, joined the camera club, and walked in the grounds. The famous psychologist William Rivers successfully utilized the ‘talking cure’ for shell-shocked officers while practicing at Craiglockhart on famous patients like the war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen.

Sassoon also remains one of the only war poets to publish on the issue of soldier suicide directly. Within his poem, he describes the suicide of a soldier whose death is never again discussed. Sassoon outlines succinctly what remains to be a considerable challenge for historians and modern servicemen and women. In 2018, eight Scottish military personnel took their own lives, prompting Clare Haughey MSP the Minister for Mental Health to issue a statement confirming that steps were being taken to support the mental health of veterans.

Military suicide is a difficult topic to research and consider, but it is also increasingly essential as service and veteran suicide rates have yo-yoed worryingly since 2003 in countries such as Britain, the United States, and Canada. My research focuses on military suicides in Britain between 1914 -2018, and so far it has uncovered many untold histories.

Dr. Simon Harold Walker is a Military Medical Historian and Historical Suicidologist who is currently researching the History of British Suicide in the Long Twentieth Century. He has published on a variety of topics associated with the British Army and Military Medicine and is releasing a book on the physical creation and transformation of soldier’s bodies in the First World War with Bloomsbury Publishing titled Physical Control, Transformation and Damage in the First World War: War Bodies. He also presents the YouTube series Feeding Under Fire, where he takes pleasure in feeding trench food to his unsuspecting guests. You can find out more about Dr. Walker and his research at his website www.simonhwalker.com

Dr. Walker’s latest article in the Canadian Bulletin of Medical History entitled “The Greater Good: Agency and Inoculation in the British Army, 1914–18” is free to read for a limited time here.

Comments on this entry are closed.