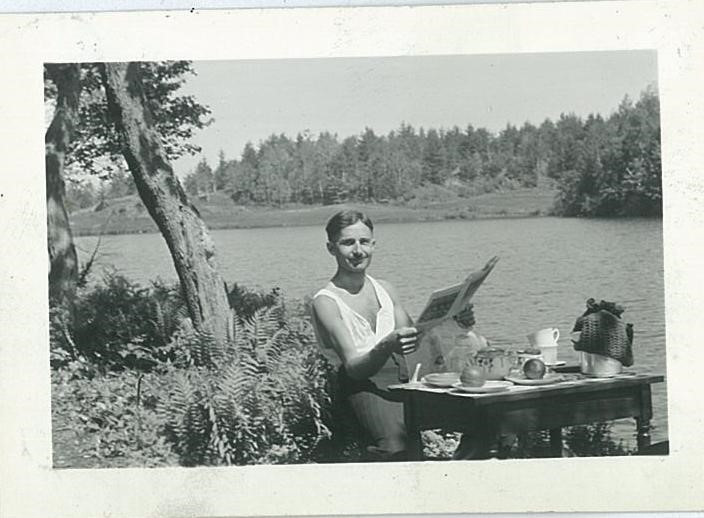

Eugene Forsey (reproduced with permission of Helen Forsey)

Eugene Forsey (reproduced with permission of Helen Forsey)

Written by guest blogger Christopher Dummitt.

If you really want to understand historical change, look to conservatives. You’ll almost always find conservatives lamenting what they see as a world under threat, and in danger of being lost. They’re not always able to convince others that the changes represent a decline or a loss. But they tend to be very adept at seeing change itself.

That’s the kind of insight I took into the writing about Eugene Forsey and his campaign to fight to make sure Canada would still be called a Dominion. Forsey was a complicated man – a young socialist in the 1930s who had helped to create the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation; a labour activist and organizer; a friend to Conservative prime minister Arthur Meighen; and a man who felt that Canada’s British heritage needed to be safeguarded. I found myself reading Forsey’s correspondence from the 1940s and 1950s for another project and became fascinated by the man, and also by his fight over Dominion.

Forsey was bilingual, progressive, and accommodating. You can find him writing in his letters to colleagues about his family obligations (about his crying or sick children and his often-ill wife). He sat at a typewriter late at night after his day at work and then in the evening with the family. I have read through the papers of many political figures from the 1950s and this is not a common phenomenon. He was a pretty interesting figure.

He also didn’t fit the stereotype we have in the historiography about a pro-British Canadian from this era. He wasn’t a narrow race-patriot. So I was curious and I dug further. And what I found is that some of the historiography is partly wrong, and needs to be made a little more complicated. My work on Forsey was a good example of what other scholars like Raymond Blake were saying about debates over nationalism in these years.

Of course, Forsery eventually lost his war. The Liberal governments under St. Laurent and Pearson and then, definitively, Pierre Trudeau, stopped using the word Dominion. In 1982 Dominion Day became Canada Day and Forsey had well and truly lost his fight.

So Forsey was, in this sense, one of Canada’s losers—a conservative (in this case) who couldn’t shift the direction of historical change. But he wasn’t (and isn’t) the kind of historical loser that many contemporary academics were likely to find compelling or sympathetic—he was a white man talking about preserving the majority culture. And so it struck me that he was exactly the kind of figure that I ought to write about—someone whose complex reality was likely to be obscured by the changing fashions of the academy.

Christopher Dummitt’s most recent book is Unbuttoned: A History of Mackenzie King’s Secret Life that was shortlisted for the Canada Prize, the Shaughnessy-Cohen Prize for political writing, and the J. W. Dafoe book prize in 2018. He is Associate Professor at Trent University’s School for the Study of Canada and the creator of the forthcoming Canadian history podcast 1867 & all that.

His latest article in Canadian Historical Review entitled “Je me souviens Too: Eugene Forsey and the Inclusiveness of 1950s’ British Canadianism” is free to read for a limited time here.

Comments on this entry are closed.