Written by guest blogger Dr. Carole Lynn Stewart.

One of the challenges in writing on American temperance (anti-alcohol) movements and literature or culture in the nineteenth century is that people often hold stereotypical ideas about white middle class, conservative Protestant, evangelical reformers—and they are not flattering. Narrow-minded, ascetic, moralistic reformers come to mind, and sometimes this is true. Of course, anyone studying or researching temperance realizes the situation is much more multifaceted and nuanced. Once we also learn that most African American abolitionists, and women’s right reformers, were also temperance reformers, the perspective changes.

I had been interested in the cultural phenomenon of alcohol and drug recovery movements earlier in my research career even as a graduate student, but the research on addiction and the body tends to garner more attention in literary and cultural studies. The more I researched, the more I came across the metaphoric expression in temperance literature of being a “slave to the bottle.” And, similar to how twentieth-century cultural texts often associated African Americans with drugs and crime, nineteenth century European American authors frequently imagined their addiction to alcohol (and other drugs) as a fearful descent into a dark metaphorical slavery. African American reformers, on the other hand, hoped that temperance could result in political, social, and economic freedoms for them – freedom from chattel slavery as a start.

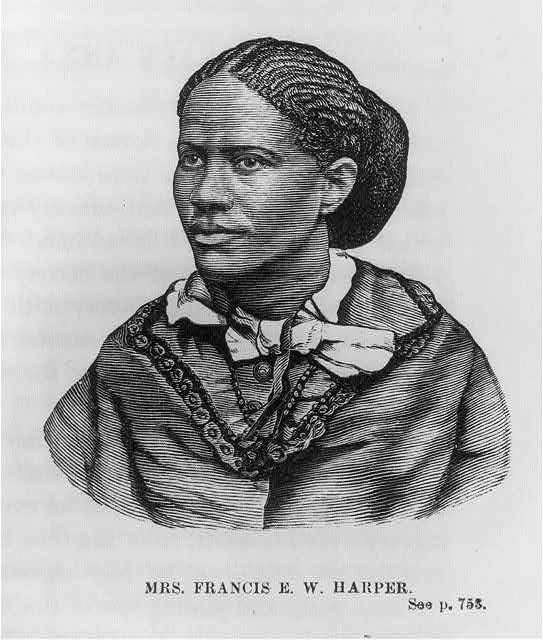

Nineteenth-century African American writers and reformers like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper were not simply parroting the values of prominent reform movements, such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), when they joined ranks, mobilized, and often resituated the discourses of intemperance. Harper was an author, activist, and temperance reformer who published several novels, most of them addressing temperance. While some of Harper’s novels and speeches are more politically oppositional to the continued oppression of African Americans through the Black Codes and lynching following the end of slavery and Reconstruction, her most famous novel, Iola Leroy (1893) does not have that reputation. In fact, it is often viewed as upholding some of the values of whiteness through its emphasis on a mixed-race couple who could pass as white.

In my book, Temperance and Cosmopolitanism (2018), I discussed the nature of creolization and cosmopolitanism in Harper’s works but was unable to delve into specific allusions to lynching or incarceration in Iola Leroy, as I do in this paper in the Canadian Review of American Studies. One of the wonderful things that occurs when teaching and scholarship overlap is that historical references begin to appear more clearly and directly in the novel. Such was the case, for instance, when I found resonances from direct speeches and historical discussion of debates on prison reform, gender, and the replacement of slavery with incarceration within the WCTU in Harper’s Iola Leroy. Although Harper shared a temperance commitment with the WCTU, my discussion shows how African American conceptions of temperance were politicized differently from the beginning, and often suggest an entire reordering of civil and political society.

Dr. Carole Lynn Stewart is Associate Professor of English at Brock University, where she specializes in American and African American literatures. She has published several articles on American reformers and literary works, and two monographs related to American religion, literature, race, and reform: Strange Jeremiahs: Civil Religion in the Literary Imaginations of Jonathan Edwards, Herman Melville, and W. E. B. Du Bois (University of New Mexico Press, 2011) and Temperance and Cosmopolitanism: African American Reformers in the Atlantic World (Pennsylvania State UP, 2018).

Dr. Stewarts recent article in the Canadian Review of American Studies entitled “Iola’s War on Alcohol, Lynching, and the Rise of the Carceral State” is available free to read for a limited time here.

Comments on this entry are closed.